Let's do great things for men’s tennis, together!

Member Spotlight

Get to know some of the NSMTA Members and Board Members. If you’re interested in being profiled or would like to nominate someone, please let us know.

If you would like to contact the author of an article below, please click on their email address.

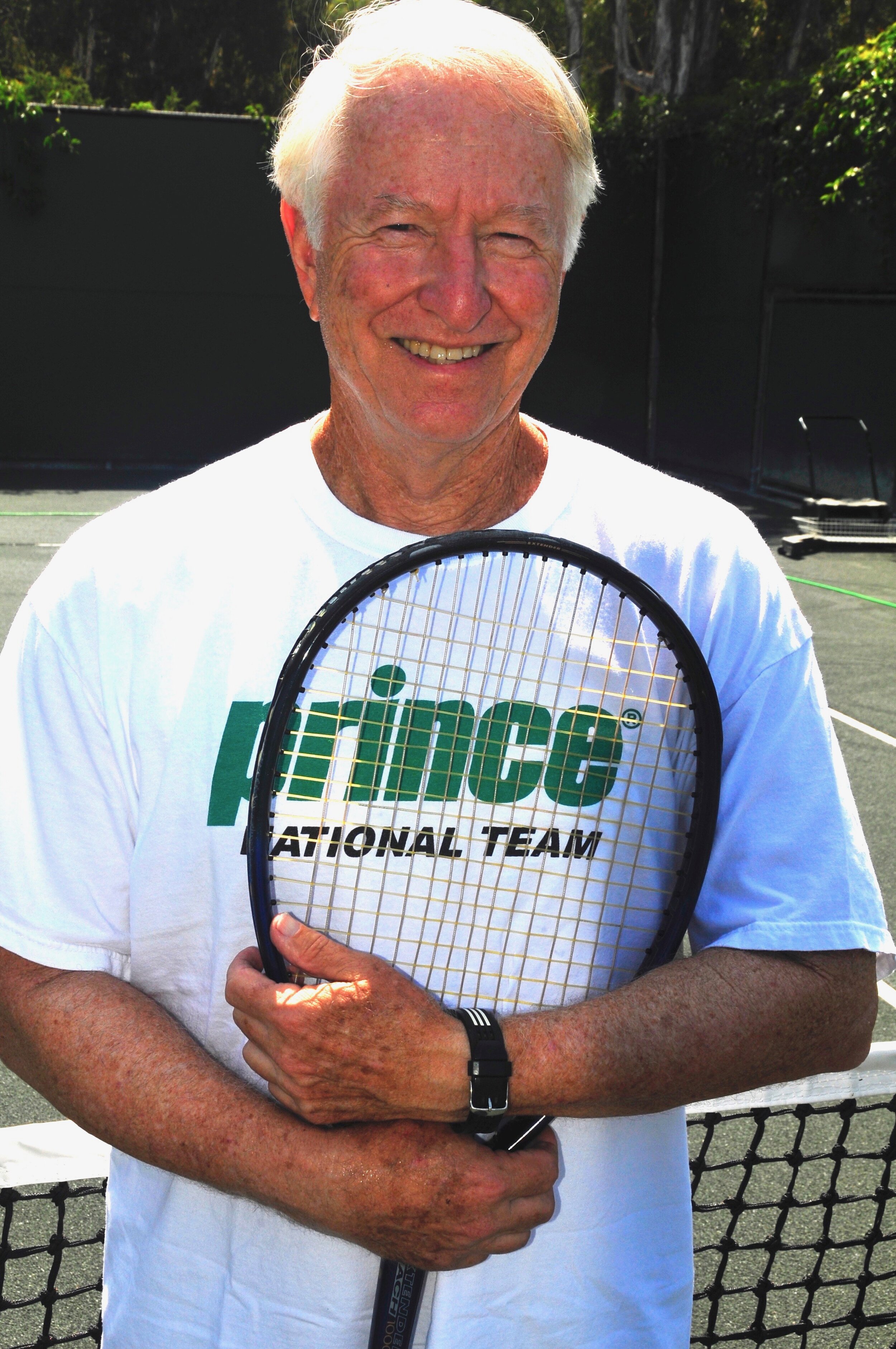

Interview with Roger North No.1 in 80s Singles

Paul Fein

October 2024

How, when, and where did you get started in tennis?

I grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey, and started playing tennis the summer before my freshman year in high school. I and three friends, who unlike me were from “country club” families and already knew how to play tennis, spent all day long nearly every day that summer at the public park tennis courts in Plainfield. Of course there were periodic diversions such as collecting bugs, throwing crabapples at each other, and generally being rowdy young boys. The father of one of my pals was a decent tennis player, and showed me how to hold the racquet, some basic footwork patterns for forehand and backhand, and how to keep score.

The court surfaces were black asphalt, and the nets were made from chain link. The New Jersey summer climate was often 90-degree temperatures and 80% humidity, but that was not a problem for us youngsters. At the end of the summer the Dad, Dr. Roland Black, organized a tournament for us and some other boys, with trophies and everything. I came in second, and still have the trophy.

In my grade school years, I was an enthusiastic baseball player—lefthanded, so of course a pitcher—before I started to play tennis, and when freshman year Spring came I wanted to play baseball. But I had an after-school job two days a week washing dishes in a local Chinese Restaurant, and I asked the coach if I could skip practice twice a week, to which he quickly replied “Absolutely not.”

So, I went out for tennis. My three friends and I all joined the tennis team, stayed together for four years playing on the 12 red clay courts that Plainfield High School had. By our senior year we had one of the better teams in the state. I never played No. 1 on that team, but did have a 19-2 record my senior year. And I was hooked on the game—for life, it turns out.

In high school, you played one of the biggest names in tennis history. Please tell me all about it.

Every year Plainfield High School played Pingry, an excellent high-end, New Jersey private prep school, which always had a great tennis team (Les Buck went there, but he is four years younger than, I and our paths didn’t cross back then). They had always shellacked us when we played.

In my senior year, when our coaches were introducing us before we played our singles matches, the Pingry coach introduced my opponent. His name was BILL TILDEN! At the time I didn’t know much about professional tennis players, but I did recognize the name, and I said to myself “Geez, I’m playing a pro! He’s going to kill me!” And sure enough, as we warmed up, I saw he had perfect strokes and seemed quite confident.

But I am stubborn, and I played my hardest and beat him in straight sets. I then realized that he was not a pro, but I did find out later that he was actually the nephew or grandson—not sure of the exact relationship—of the real and great Bill Tilden! So now I can say, “I ONCE BEAT BILL TILDEN.” Ha!

Oregon is not known as a tennis hotbed. If I’m correct, what has held it back? If I’m incorrect, please tell me why, and who have been its top male and female players.

It is definitely true that the Pacific Northwest section (Oregon, Washington, Idaho) has not had anywhere the success in sending tennis players on to the professional tour as Florida and California, but there have been a few exceptions that come to mind. Pat Galbraith and Tom Gorman from the Seattle area, Jonathan Stark from Medford in southern Oregon, and Travis Parrot from Portland. Travis was a doubles specialist on the tour who in 2009 teamed up with Carly Gullickson as a last-minute wild card mixed doubles entry to the US Open, and they went on to win the tournament.

I played a number of times next to Travis on a court at the University of Portland where he practiced. But I try not to take all the credit for his US Open title just because I once pointed out to him that he was foot faulting while practicing his serve. Travis laughingly informed me that he was working on his weight transfer and knew he was stepping over the line. My friend who I was playing with was appalled and embarrassed that I would have the gall to say something like that to an actual tennis professional.

Perhaps the area’s lack of very successful tour pros is due to the Pacific Northwest’s somewhat chilly and very wet winters and springs. But there is also a thriving tennis community all around Oregon and Washington, due to the many clubs, both public and private, that have both outdoor and indoor courts. The beauty of that is that one can play tennis regardless of the weather all winter and spring.

There are also several area senior players who are world-class competitors, most notably Mike Tammen now in the 65+ bracket, Len Wofford and Paul Wulf in the 70+, Ken Dahl and Don McCormick (both from nearby Vancouver, BC) in the 75+ and Jody Rush in the 80+.

You played college tennis at Swarthmore in Pennsylvania. Ed Faulkner, the author of the acclaimed 1970 instruction book, Ed Faulkner’s TENNIS: How to Play it, How to Teach it, coached the men’s team. What were the highlights of your competitive career there?

Swarthmore is a small but intense college in the Philadelphia area. Despite the fact that there were no athletic scholarships offered in any sport, and that there were no easy courses in the curriculum, Swarthmore had, and still has, a decent tennis team.

When I applied to go there, I did not realize that they had a legendary tennis coach—Ed Faulkner—who had played with and even had a couple of wins over Bill Tilden (the real one, the 1920s superstar), and who had coached both the French and American Davis Cup teams before retiring from playing and teaching tennis into the coaching position at Swarthmore. At that point in his career he wasn’t, at least to us, doing much actual teaching aside from the occasional technical and strategic advice he tossed out. I think he accurately assessed that none of us would ever become world-class tennis players. But he was respected and inspiring, and a few things he said have stuck with me: “Don’t change a winning game,” “Hit the ball on the rise,” “Clear the net by at least two feet,” and the best advice of all—“Win the last point of the match.”

I think where I was concerned, he observed (politely) that my strokes were “non-classical,” but that I was a quite intense competitor who never gave up. So, I think that because he encouraged my strengths—I was fast and my moonball game was quite effective on our clay courts—I was able to beat a pretty good number of players who I felt were better players than I was.

Faulkner likely regaled you and your teammates with fascinating stories about his most famous students and tennis friends. Which stories do you remember?

I don’t remember too many of his stories, but one has stuck in my mind that comes from his playing days. (He was in his mid-60s when he was our coach and had lost the vision in one eye and was no longer playing.) As he told it, he had lost the first set to a very good player (whose name I don’t remember) who was quite religious and was a strict non-drinker. Knowing this about the player, Ed had prepared for the match by filling an empty whiskey bottle with some dark tea. When the first set was over, he decided to pull out the bottle and very visibly take a swig from it on every changeover for the rest of the match. Apparently it filled his opponent with shock and disgust to the point that his game fell apart and Ed won the match. Not exactly textbook tactics, but it was indeed effective and funny.

Did you play men’s open tournaments in your 20s and 30s? If so, how did you fare?

When in high school and college I played in a number of club and local tournaments in the Plainfield area, which were fun and competitive, but not that high a level of tennis. Then after I graduated from Swarthmore in 1966 and moved to Boston for graduate school, I pretty much stopped playing tennis. At that point I was too busy with the studies and had lost my tennis network and wasn’t up to building a new one. Also, this was 1967, and I became involved playing music in the Boston club scene (I had been playing drums in bands since seventh grade) and so no more tennis for a while—until 1983 in Portland.

In what profession did you earn a living?

I was trained as a structural engineer, and worked in Boston as one for two years after I got my Master’s Degree. But then, my musical career started looking more promising, and my engineering job became half-time for six months, soon after which I became a fulltime musician. My band, Quill, was traveling around the northeast states quite a lot, and while there was not a lot of money, I guess you could say I was (barely) earning a living. So still no tennis, but we did play on the main stage at the Woodstock Festival in 1969, which was memorable. I then went on to play with several other music acts (Odetta, Holy Modal Rounders, Freak Mountain Ramblers), and moved to Portland, Oregon, from Boston in 1972 on the band’s bus.

My son was born shortly after. In Portland, I started a small company manufacturing a new type of musical drum which I had invented, played, patented, and eventually began selling around the world. I modestly called them “North Drums,” and there is still a small but loyal cult of North Drum owners and players. Some famous ones, too. You can Google “Roger North Drums” and learn what that was all about.

When did you decide to compete on the USTA senior tour? And why?

At age 40 (1983), I decided I needed to start actually earning a living that would support a small family, so I rejoined the corporate world and took a job programming computers, and then being a database designer/architect. I also missed the athletic part of my life, and so I joined a tennis club and started playing my favorite sport again. By the time I was 50, I learned from some fellow players about the USTA senior tournament circuit around Oregon and Washington and began playing in them. I realized then how much I loved to play tennis at a competitive level.

Later, after I had retired from my computer job and had cut my musical endeavors to a more civilized level of one local show per week, I started traveling to sectional and national tournaments. My first such event was in Palm Springs when I was in the 65+ bracket.

What do you like most—and least—about playing sectional and national senior tennis tournaments?

I have really enjoyed the very satisfying combination of serious competition and friendshipthat resulted from traveling to the tournaments—as a coach of several baseball teams that my son Tye played on in his adolescent and teen years I always tried to make the boys recognize that they could be intensely competitive without considering their opponents on the field to be their enemies. I was always proud that the boys seemed to eventually come to realize that they could, and often did, become good friends with the fellas on the other teams. In the tournaments that we play in now I see that kind of competitive friendship everywhere—we are all coming up through the age brackets together and it feels good to meet men with that and many other things in common with my own interests whom I would otherwise never have met. That’s very fulfilling and fun!!

I would also like to say that I have come to appreciate all the work that the various tournament directors and volunteers who do the work that makes all these tournaments possible. I try to take the time to thank them at every tournament, and I would encourage the other players to do the same—it’s really a big deal in all our lives that they take the effort to provide this great environment for us to get together, compete, and enjoy each other’s company.

The tough part is that travel to tournament sites is not cheap, and I sometimes have trouble justifying the expense, although my son is grown and I am single and have, thanks to my re-entry into the corporate world, some retirement funds that make it possible to do (within reason).

Who are the best senior players you’ve played in singles and doubles? And what makes them so hard to beat?

There are a good number of them. In singles, I’ve really enjoyed meeting and competing in singles with Ray Lake, Dave Dollins, Henry Steinglass, Bob Mason, Don Long, Jimmy Parker, Fred Drilling, Paul Fein, Les Buck, Hill Griffin, Peter O’Brien, BJ Miller, Ed Elkin, Mike Saputo, Tim Carr, Bob Quall, Ben Murphy, Jody Rush, Leo Lapane, Dave Schermerhorn, George Kraft, and countless others stand out. In doubles, Dean Corley, Michael Stewart, George Balch, Bob Shineflug, Steve Lunsford, Tim Shum, Danny Miller, Dave Berg, Karl Placek, Tony Pausz, Dave Vandenberg and many of the above singles players have been memorable. And of course, I always enjoy playing with my regular doubles partner John Popplewell and my longtime friend and valued practice singles player Mike Stone, both of whom live in Portland.

All of these players have been hard (sometimes impossible) to beat. Each one has a unique set of strengths and liabilities, which makes it really interesting and a great mental and physical challenge on the court. Almost all of them have beaten me, some I have managed to beat. But equally important is that I have enjoyed spending a bit of off-court time with and am fond of all of them. This has been a great part of my life!

Please tell me about your best wins—who you beat, the score, the name and place of the tournament, and what was most memorable about the match.

In my senior year in college, we traveled to Annapolis to play the Naval Academy team, which had always beaten us badly in tennis. The day before we went down there, I came down with the flu. I had a pretty high fever and felt really really bad. But I didn’t say anything because I wanted to play. I was the No. 3 singles player, and I had to play a fellow who (I was told) was also the quarterback for the Navy team that year (I don’t remember his name). Turns out, I played quite well—perhaps the fever gave me extra energy—and won that match and then teamed with our No. 2 singles player to win the No. 1 doubles.

Afterward, I went into the locker room, lied down on the shower floor, and nearly passed out. But Swarthmore beat Navy for the first time in many years, and that was a good ride home! I also beat Bill Tilden in high school.

Recently, you decisively upset No. 3 seed Dave Dollins 6-2, 6-4 at the National 80 Clay Court Championships at Virginia Beach, Virginia. What were the keys to that big win?

The weather was gruesome this year at Virginia Beach, and most of the matches were played indoors. I really think this worked in my favor, as I have played indoors many many times and am comfortable with it. Perhaps Dave Dollins, being from Southern California, was understandably less comfortable with it. In any case, I felt that I played pretty well, and as sometimes happens, it seemed that quite a number of balls that I hit near the sidelines stayed in. Yay! Also, Dave almost never misses a shot, so I did follow more shots to net than I usually do, and that worked well that day. He’s really a tough player. We got to spend some time together in Virginia Beach, and we have become friends.

Your success there boosted you to No. 1 in the USTA National 80 singles rankings. When you were a teenager playing junior tournaments and then competing on the Swarthmore team, do you ever imagine you would rank No. 1 in the U.S.?

I never even remotely thought about it. I don’t think I ever thought about being 80 years old either. By the way, I fully recognize that the USTA ranking system is quite flawed, and is not a good indicator of the tournament records and relative strengths of players. The rating systems of UTR and ITF are far better in accurately determining how strong players are.

On the other hand, it is fun to be able to tell my non-tennis-savvy friends that I have a high national ranking. HA!

If Ed Faulkner were alive now, what do you think he’d say to you about your feat?

When I returned to Swarthmore a few years after graduation with my band to play a concert, I visited Mr. Faulkner, and he said “I always thought you might become a professional musician.” I suspect he said that because in my senior year on the night before the conference championships finals, I persuaded the assistant coach, Lou Gaty, to drive me 150 miles back to the college so I could play a late-night music gig before returning to the finals early the next morning.

I’m sure Coach Faulkner was not happy with me for doing that. But my partner and I won the doubles championship the next morning, so I got away with it.

If Mr. Faulkner were asked about me being ranked No. 1 even briefly, I would guess that he would NOT say “I told you so.”

BJ Miller “Engineers” a Vocation and an Avocation

Paul Fein | PFein@nsmta.net

August 2021

What do your initials stand for? And when and why did you decide to abbreviate your forenames?

My name is William James Miller, named for my grandfathers. Even though one of them died well before I was born, I was called “Billy Jim,” to offend neither. That lasted until about the fourth grade, when classmates started calling me BJ. Try high school with that abbreviation.

Did you come from a family that played sports a lot?

No. My biological father, who died when I was six, played tennis, but no one else. My mother could have played quarterback or any other position in any other sport in which she was in charge. She was not particularly athletic, but she was always in charge.

Where did you get your higher education?

I went to Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee, where I got a B.E. and M.S. in Civil Engineering. I also got hooked on bluegrass banjo, mostly from watching Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and the “Foggy Mountain Boys” live on TV every Saturday at 6 p.m.

I once visited Earl at his home in the suburbs. He sat patiently and described how he played the “Be it ever so humble” line in “Home, Sweet Home.” When he died a few years ago, many banjo players, including Steve Martin, told a similar story of meeting Earl and having him take the time to show them a few licks.

Then, I went to UC Berkeley and got a Ph.D. in Civil Engineering.

What exactly do Civil Engineers do?

They generally focus on either designing civil works or planning for them. I chose the latter. I worked on regional plans for water and wastewater facilities, then served several years on California’ State Water Resources Control Board, and then became a private consultant, working from home on California water problems. For about 25 years, I also taught a one-day course, “The Management of Water in California,” for the University of California Engineering Extension.

The West and Southwest suffer from an extreme drought. If you were the Czar of Water Management in California, what changes in our current water policy would you espouse? And why?

First, I think it’s very hard to get anything done in California water. At its core, managing water is a scientific—mostly biological—and engineering matter, transcended by ideology, activism, and politics. Almost every proposed project is burdened by concerns over its capacity to adversely affect interested parties by mis-operation.

Second, California is a highly altered system when it comes to water. All the major rivers have been dammed more than once. Canals convey water from the water rich north and east to the water poor south, central, and west. The largest tidal marsh on the west coast, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, at the confluence of the two rivers draining the great Central Valley, has been converted to agriculture; its waters are now dominated by non-native species at all levels of the food chain. Attempts at “restoration” (usually a misnomer for “conversion” or “improvement”) are heroic and, so far, feeble. The competition for water, aggravated by the increasing frequency and severity of floods and droughts due to climate change, is fierce and growing more so. California has no choice but to manage its water and the environmental effects of supplying water.

If I were czar, my highest priority would be to avoid assassination. Assuming success with that, I would do the following:

*Negotiate several statewide agreements to provide certainty to environmental interests, water users, and others with much at stake. The primary one would be to settle the long conflict between northern and southern California over water. Such agreements may sound far-fetched, but it’s likely that the substance of those agreements would not be as contentious as the provisions to ensure compliance with them.

*Federal and state Endangered Species Acts would now override any such agreements, so those agreements must include provisions that would use discretionary aspects of the two acts to make them part of each agreement. Such agreements would lift the political, ideological, and suspicion-ridden burdens now being placed on construction of projects, for environmental and water supply purposes, necessary to meet problems presented by climate change.

*Create a science program, including monitoring programs, directed primarily at supporting those agreements, with safeguards to avoid the all too frequent intrusion of ideology into science. These unique safeguards would be essential to the agreements’ certainty.

*Create a statewide water bank where sellers and buyers of water can efficiently transact business for both short-term and long-term transfers that kick in whenever water is scarce. Incorporate authority within the bank to ensure protection of environmental interests and avoid adverse socio-economic effects on areas from which water is sold. Such authority already exists and could be used as is or modified as appropriate, especially to streamline the process of buying and selling water.

*Create high school classes to explain to students how their basic utilities—water, power, transportation, wi-fi, and the like—work

You didn’t start playing until age 30. How did you happen to discover tennis at that relatively late age?

I don’t know. I had always dabbled in tennis. As a kid, I laid out a tennis court in our large side yard. I had played lots of ping pong, so I started playing tennis with a Continental grip and just transferred ping pong to the tennis court. I had played basketball, a moral obligation growing up in Kentucky. I had played a lot of golf, too, and liked the solitude of that sport and tennis. I did not come to appreciate tennis as much as I do now until later. Maybe it had something to do with my Dad, but I’ll leave that to the psychologists.

What appealed most to you about tennis?

I can’t put my finger on the initial appeal. Now, I have many reasons. Tennis is a wonderful endeavor, and once retired, an endeavor is an important source of happiness and sense of accomplishment. I have many tennis friends. I love to practice, and that really pays off in tennis. I think that at almost any age, you can get better if you engage in purposeful practice for a few months. Tennis is also great exercise. I like the civility of it, the code of honesty about line calls, and the severity of adverse opinion about those who make bad calls.

If you took lessons over the years, which coaches or teaching pros helped you the most? And, specifically, how?

I took lots of lessons from many teachers. Michael Wayman was the best. He is very smart and believes there are many ways to win at tennis. The lessons started with winning—we would play points, he at my level, and it was like drinking from a fire hose.

Michael would tell me the shot I should have hit to have the best chance of winning the point, why I was unable to hit it, and what I had to do to master that shot. He was death on preparation, especially the early (unit) turn and setting the racket in the hitting position early. He never told me anything that was wrong.

He lives near Jimmy Parker in Santa Fe, and they hit together. They have a similar approach to the game, fiercely competitive and shameless about hitting any shot that is effective and within the rules.

I recently had a couple of lessons with Greg Smith, who teaches in Indio, and I’ve had many email exchanges with him. He worked for years with Vic Braden. He understands the kinetic chain, what it actually is as opposed to the incomplete explanations I often see, and has changed my concept of how power is generated in tennis.

You live in Oakland, California, and the Bay Area has long been a hotbed of tennis. How much did that history and tradition figure in your passion for tennis and eventual emergence as a successful tournament player?

I’ve been a member of the Berkeley Tennis Club for more than four decades. It is steeped in tradition and full of good players, especially senior ones. In the 2019 National Hardcourts, the Berkeley Tennis Club had four members in the round of 16. We all lost in the quarters.

However, I can’t say I’m much of a fan of tradition. For that matter, I not a big fan of pride in one’s culture. All culture’s, mine included, have some despicable and commendable features. I think we should cherish the commendable ones, ditch the others, and focus more on how we function now in the world and less on culture.

Where do you usually practice? And who have been your favorite practice partners?

I practice at the Berkeley Tennis Club. I have regular hits or matches almost every day. I hit with the ball machine a lot, working on common but unpracticed shots, like drop shots, underspin angles, topspin lob groundstrokes, serve returns, half volleys, lob volleys, and others. The ball machine is my favorite practice partner.

Do you enjoy “talking tennis” with them? And what do you talk about most?

All of my tennis friends like to talk tennis, but there are two kinds of talkers: There are the ones who like “general tennis talk”—who won matches on TV, interesting points, how players competed—the stuff you hear from announcers. Then, there are a few who can tolerate the deep stuff—grip pressure, split step timing, accelerating through ball contact, the kinetic chain, waiting for the ball, etc.—the stuff that most players have little patience for.

What are you most proud of as a senior player?

I am most proud of radically changing my game in my first year in the 75s. I did not think I could stay with the leading nationally ranked players playing typical tennis, exchanging ground strokes and grinding it out. So, I decided to come in on every one of my serves and every one of my opponent's serves. I returned from about three feet behind the service line and spent hours practicing those returns, especially the techniques required to deal with the lack of time to execute a return.

I sent out an email to about 50 tennis club members saying that if they wanted to practice their serve, I wanted to practice returns. I got a lot of takers—damn near got killed by one of the good, young women players.

I won the first two January matches in the Palm Springs tournaments, got injured, and lost in the big Cat II tournament at Mission Hills. I played several matches in which I never hit a ground stroke. I lost in the National Grass Court semis in a third-set tiebreaker with a heat index over 100 degrees. I was wiped out for a couple of months.

When I began to understand, at least partially, what Jimmy Parker was doing, of almost giving up his former, beautiful, tour-level game for one that was more suitable to his and his opponents’ talents, and of the reluctance of most players to change their games in even far less radical ways in order to win, I grew increasingly impressed by what I had done. Then I recalled how well my game worked against Jimmy, and I fell back to earth.

You’ve described yourself as “a nationally-ranked senior player with a well-deserved reputation for obsession with tennis details.” Where does this “obsession” come from? And how has it influenced your technique and tactics?

The “obsession,” a pejorative term—even though it was my own—seems to me to be the logical path to improvement. Tour-level players are so good because they do hundreds of little things correctly.

I heard a long interview with the British cycling coach after they had won the Tour de France twice in five years. He said they broke cycling down into its component parts—bike set-up, riders’ clothing, riders’ position on the bike, riders’ physical training, riders’ diet, etc.—and, for each player, they looked for very small, one percent improvements that each player could make.

Maybe some tennis players do that instinctively, but most of us don’t. For us, focusing on the details with purposeful practice can pay big dividends. But there is no moral obligation to do so.

Tennis is, after all, just a game, and it can be approached without any obsession about details.

Why did you take a great interest in my new tennis instruction book, The Fein Points of Tennis: Technique and Tactics to Unleash Your Talent, from the start? And what aspects of it did you help improve?

I was flattered to be involved. You were kind enough to send a draft and ask for my opinion. I thought the book was really good. When I apologized for making some critical comments, you said that’s what you wanted and that you would not be offended and, of course, might not agree. I remember thinking, “This guy is a pro, and that’s what the really good ones must do.” From then on, I was glad to do anything I could.

I started drafting captions—which you would improve—for the 100 or so photos, trying to explain what each player was doing, you know, obsessing about details. It was a fascinating exercise. I tried to incorporate facts about the kinetic chain. I learned a lot, mostly about how good players are almost always on balance—and what balance is—torso vertical, centered between the legs. I learned how they go intentionally off balance for initial speed, and how power comes not from the arm and hand but from rotation of the core, which requires being on balance. So, I was very grateful you let me contribute.

Who have been your favorite tennis players over the years? And why have you liked or admired them?

I like three types of players. One is players who play with variety in their games. I’m bored with players grinding it out from the baseline.

Another is players who aren’t carried away with themselves, who are humble and respectful of their opponents.

Third, I generally like watching women rather than men, just because they play more like we normal mortals, not that I could stay on the court with any of them. So, my favorites now are Ash Barty and Bianca Andreescu and, of course, Roger and Rafa. There are a number of others, but those are my current favorites.

Which tennis books of any kind have you enjoyed most? And why?

I have not read many of them, although I watch YouTube videos. I’m more of a listener than a reader. I liked Tilden’s Match Play and the Spin of the Ball and Talbert and Old’s The Game of Doubles in Tennis. I’m reading The Pros, The Forgotten Era of Tennis, about the barnstorming pros in the time before open tennis. It’s a wonderful book. The five opening paragraphs in Chapter 2, ostensibly about tennis, could well serve as instruction for life. I subscribe to John Yandel’s website, which has really good stuff.

Which TV tennis analysts do you consider the most knowledgeable and fair? And why?

I have big problems with tennis on TV. I think most people who watch also play and would love more detailed comments about what players are doing. It’s as though the commentary has been dumbed down so that people who don’t play can enjoy it, but that’s not what other sports do. I like some commentators—Brett Haber, Jimmy Arias, Darren Cahill, Martina Navratilova, and a few others—the ones who are knowledgeable and self-deprecating.

What is your opinion about thinking while playing?

I often hear that I think too much—you know, obsessed with details. I do it because it’s interesting and often because it seems necessary. I have been the same way about golf, bluegrass banjo, and my work on California water problems.

I have played some matches where I was “in the zone”—time slowing down, focused, no distracting thoughts, but that is not a familiar state for me. Usually, though, I see tennis as a 1½-to 3-hour exercise in problem-solving. What works against my opponent? What is he doing to me? How can I counteract it? Why isn’t my serve going in? Why did my last three backhands go into the net? If such questions are not arising, I’m having a really good day, but good opponents usually don’t let me have good days. In that case, it’s think or lose, so I think.

But I know that many players just play. Their games developed over many years. They played good tennis when they were young, and their good habits are hard-wired. Mine are often hanging on by their fingernails. That’s probably why coming in on my serves and my opponent’s worked for me—no thinking.

Ideally, we would think during practice and not too much when competing. But if you’re competing and things are not working, you’d better think about how to change things.

Golf commentators often laud playing without thinking; then we see a player who just pushed the last two drives 50 yards right, standing on the tee, rehearsing the next drive. That player is thinking and will think during that drive.

What do you enjoy most about senior sectional and national tournaments?

I like the competition. I like watching matches and talking with other players about the matches and tennis in general and also about non-tennis subjects. These tournaments, especially the nationals, are like reunions. The social aspect is the most enjoyable.

These reunions are interesting because tennis is such a hierarchical sport, and that carries over to the social part of tournaments. There seem to be two main criteria that determine the respect and friendships that players enjoy: Can he play and is he a good guy? Good guys are gentlemen on the court and modest off of it.

Do you have any suggestions to improve any aspects of senior tennis, including the National Senior Men’s Tennis Association?

I have two, neither of which seem too practical: One is to find a filthy rich benefactor who would endow senior tournaments, providing enough prize money to attract really good players and to offer all participants some reward for playing.

The second harkens back to the days when the Berkeley Tennis Club hosted the Pacific Coast Tournament, where the best players in the world would come. The club members did a lot of the work, housing players, providing meals, transporting them, and generally trying to make things as pleasant as possible. It was a great social event for the club. Members met and worked together with other members and made the club stronger by doing so.

I think senior tournaments could attract more players if players knew they were going to have an experience something like the touring pros, significantly scaled back.

I have nothing but good things to say about the National Senior Men’s Tennis Association.

Paul Fein: Tennis is his racket as a writer, coach, promoter, and player

Ed Trost

etrost@gmail.com

June 2021

Paul Fein (right) interviewing Martina Hingis at the Ocean Edge Resort in Brewster, Massachusetts, in July, 2004.

(Photo credit: Tim Balestri)

“Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depth of your heart; confess to yourself you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.” – Rainer Maria Rilke, Bohemian-Austrian poet

Considering that in Paul Fein’s fourth and latest book, The Fein Points of Tennis: Technique and Tactics to Unleash Your Talent, each chapter begins with an aphorism, I thought it appropriate to begin this piece with one that aptly describes Paul’s passion for the art of the written word. His enthusiasm for the sport of tennis was evident in his voice as he spoke with me about his career as well as his prolific writing on the subject over the past 40-plus years.

Although Paul didn’t compete in New England tournament tennis until his last year of the juniors, it didn’t prevent him from making the tennis team at Cornell University where he was “blessed” to be coached by the legendary tennis player and coach, Eddie Moylan. Moylan was a member of the U.S. Davis Cup Team, Davis Cup Coach, and winner at the 1955 Pan American Games with Art Larsen in doubles. Paul was an “eager learner” and, in the parlance of today’s athlete who has undeveloped potential, he was a “project” for Moylan.

After college and a stint in the U.S. Army where he was stationed in Korea, Paul worked at The Bridgeport (Conn.) Telegram as a general sportswriter. But his heart was in writing specifically about tennis, and the Tennis Boom of the 1970s proved to be an auspicious time for a budding tennis journalist. It was difficult, though, to make a living writing only for American magazines, so he first wrote for tennis magazines in England—a monthly “Letter from America” column—Japan, and Australia. He supplemented his income working as a USPTA teaching pro in Connecticut and Florida.

The reach of Paul’s writing is impressive as his writings have appeared in 30 countries and well over 100 different magazines and newspapers. He considers himself fortunate to have made a career doing what he loves as many foreign tennis magazines as well as American national and sectional tennis magazines have died this century, and most major newspapers no longer have a tennis beat writer.

As one might expect, Paul’s identity is intrinsically tied to all things tennis. He founded and directed one of the first five “satellite” tournaments in the world, the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, in 1971, which Larry Turville won. He also served the game as president of the Springfield Tennis Club and Springfield Tennis Council, tournament consultant and ranking committee chair for USTA/New England, and vice president of the United States Tennis Writers Association.

Paul considers himself not only a writer of tennis but a player, an editor, a coach, a teacher, and a student of the sport. Combine that identity with a deep love of history, politics, and current events and a proclivity to write Letters to the Editor to newspapers, it’s no wonder that he is sometimes considered by others as “outspoken” on the great issues of politics and tennis politics, whether it’s the ranking or scoring systems, seedings, or the on-court coaching legalized in women’s tennis. Inspired by Gladys Heldman’s brilliant columns in World Tennis magazine, Paul made the case for equal prize money for men and women in a 1977 essay published in Inside Women’s Tennis magazine.

It comes naturally to Paul to speak his mind based on facts and analysis, and it requires courage to do so. To wit, one of his favorite aphorisms comes from Lady Astor: “The main dangers in this life are the people who want to change everything—or nothing.”

Over the course of his career, Paul has received more than 40 writing awards, including Tennis Week’s “International Journalist of the Year” award for his Arthur Ashe interview in 1991 and several First Prize awards in writing contests sponsored by the United States Tennis Writers Association.

For those of you who love reading about tennis, whether it’s stroke analysis or tactics or award-winning articles that Paul has done over the past 40 years, then his upcoming book, due to be released in July, is an absolute must-read. This opus has 500 oversized pages, 190,000 words, 100 action photos, and is published by Coaches Choice, a pure sports publisher.

As Dick Gould, the legendary tennis coach of Stanford University’s men’s team, states in the Foreword to the book, The Fein Points of Tennis is a must-read for coaches, players, and any lovers of tennis. Paul nails it in this book and shows he is one of the very best writers of our generation.” One would be hard-pressed to find a more respected name in the tennis world to give such a glowing endorsement.

When Paul is not writing, he does find time to hone his own game. For Paul, senior tennis has been “a godsend.” When he stopped playing tennis at the age of 33, he had no thought of playing tournament tennis again. But after a 30-year hiatus, he was encouraged by a friend to get back out and play some senior tournaments.

His debut in senior tennis at the age of 63 was memorable. He drew the No. 1 seed in the New England 60 Sectionals and beat him 6-1, 6-1. In Paul’s mind, what was most impressive about the match was not his victory. Instead, it was his opponent’s graciousness in defeat. After Paul said, “I know you’re an excellent player, but you just had an off day,” his opponent replied, “Paul, you made me have an off day. You played a great match.”

That compliment gave him the confidence to continue to play tournaments. So, what happened after that initial match? Well, as Paul describes it, he wasn’t accustomed to tournament schedules, and he overslept and was defaulted in his second-round match.

Nonetheless, his competitive nature ensured he'd continue his journey on the senior circuit. After elbow and shoulder surgeries derailed him in the 65s, Paul rebounded in the 70 and 75 divisions. He peaked by reaching the 2019 National Clay Court Championships 75 singles semifinals with a big win over Fred Drilling, ranked No. 2 nationally, and he wound up with a career-best No. 5 national ranking,

It was difficult to extract very much about Paul’s personal life outside of tennis, but he did confide that in his hometown he is “semi-famous for consuming 11 ounces of blueberries daily.”

Given this proclivity for blueberries and tennis, the following maxim by author Jacqueline Mitchard seems to work quite well: “You’ll never regret eating blueberries or working up a sweat.”

* * * * * * *

You can pre-order an autographed copy of The Fein Points of Tennis: Technique and Tactics to Unleash Your Talent by emailing Paul at lincjeff1@comcast.net

John Popplewell: A Tennis Player for All Seasons

Jake Ten Pas

jake.tenpas@gmail.com

February 2021

This article was originally published in The Winged M magazine, November 2020

John in Antarctica, November 2018

Age is in the eye of the “be older.” A spring chicken by almost any definition, MAC Tennis titan John Popplewell is, at the age of 78, just hitting his stride. Over the summer, he received the dual honors of making the club’s Gallery of Champions and being selected by the United States Tennis Association (USTA) to represent the U.S. at the International Tennis Federation Super-Senior World Team Championship in Mallorca, Spain.

Asked which honor means the most to him, Popplewell appears to hold a rally with himself in his own mind. “Long-range, the Gallery of Champions has been a goal of mine since I walked through the front door in 2005, and I’m pretty ecstatic. I’ve seen the people chosen for it, and thought it was a pretty tough deal to get in.”

On the other side of the court, “It’s an incredible honor to be picked as one of four people in the whole country for my age group. I figured I’d make the team when I was in my 80s, but wasn’t so sure I’d make it this year. I want the biggest and best, and I want to win at the highest level. That would probably be it!”

On whichever side of the net the ball falls, Popplewell puts both achievements into his sporting-life top three, along with being inducted into the Southern Oregon University Sports Hall of Fame in September 2017. While he’s always been goal-oriented, competitive and ambitious, even Popplewell, Pops, or just Pop — depending on who’s talking — might not have been able to predict just how far the game would take him when he first started playing on Coos Bay courts as a seventh grader. Back then, the age of 40 seemed ancient, and being the talk of the local barbershop a noble and lofty pursuit.

The Serve

It was in college that Popplewell first realized tennis could be a sport for a lifetime. He remembers buying magazines such as World Tennis and following all the scores of guys playing around age 35 or even, gasp, in their 40s.

“At the time, when I was 18, I thought 40 was really old. Now, I figure maybe it’s not so old,” he says, laughing.

In the 1950s and early ’60s, he recalls, Marshfield High School’s teams were very competitive, and often victorious, against the best sports teams in the state. Coos Bay was a small logging town, and Popplewell remembers walking to the barbershop and listening to men getting their hair cut and talking enthusiastically about sports, particularly football. That made a big impression, and living across the streets from tennis courts and a baseball field, with a swimming pool just up the street, didn’t exactly dissuade him from pursuing athletic glory. He started playing basketball and baseball in the third grade, and was eventually introduced to tennis by his best friend, Larry Eickworth.

Marshfield High School 1959 State Runner Up team. John Popplewell, Gary Gehlert, Dale Hartley, Karl Coke and Larry Eickworth (left to right)

“I was just a little guy, 5’6 at my tallest, and now I’m 5’5”, but I knew I wanted to letter in high school my freshman year,” he says. Initially earning the spot of sixth man early that season, his buddy’s bad luck would turn out to be his opportunity. Playing against Springfield High School, Eickworth won his match, and went to jump over the net to shake his opponent’s hand. He didn’t quite make it, and severely sprained his ankle.

“I got moved to the number five spot, played the necessary amount of matches, and lettered. I was one of two freshmen at Marshfield who did, and we had 300 kids in each grade. Here I am, small for my age, wearing my letterman jacket, and I said, ‘OK, I’m all in for tennis.’”

Each year, he steadily improved, jumping up to number one on the team his senior year. He also lettered in basketball and played American Legion baseball. By the time he made his way to Southern Oregon, his love of athletics was firmly cemented. Waiting there was a familiar face with whom he would begin to cast his gaze further into the future.

The Return

Eickworth was already ensconced at SOU when Popplewell arrived after spending his freshman year at Oregon State, and the two were soon roommates. After taking a year off due to eligibility requirements, Pop was ready to compete the following year.

College action shot of John playing in a match vs. Oregon

“Eickworth and I decided at some point that we were going to be buddies forever, and so when we hit our 50s, we’d go out and start winning national championships together in doubles,” Popplewell recalls of their strong bond.

But first, there was the small matter of getting through college, and Pop decided to make the most of it. His first year playing tennis for SOU, the team took on OSU and pulled off a huge upset. They went on to beat other NCAA schools such as Seattle University and University of Oregon.

“It was a big deal because we were an NAIA school beating NCAA schools. Our team didn't lose a league match in four years. We qualified for two NAIA National Championships in Kansas City, Missouri, and we finished eighth overall my last year there.”

Following graduation, Popplewell went on to a successful career at Portland’s Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. After 28 years, he was able to retire at the age of 52, allowing him to get back to his real interest, tennis. While he’d found a home for his career, it would be a few more years before he’d find an equivalent nest for his athletic ambitions.

A Rest

Popplewell and Eickworth never did achieve their goal of being doubles champions together in their 50s. In 1990, they won the Idaho Men's 45 Open State Championship Title in Sun Valley. Three years later, the fair-skinned, red-headed Eickworth passed from melanoma.

Pop recalls meeting him on the Gallatin River, where Eickworth and his wife had a summer place. “Unfortunately, I’ve got to go to the oncology center in Woodlands in Texas to deal with cancer,” his friend confided.

“I retired at 52, but I didn’t have him as a partner, and he was phenomenal,” Popplewell says. “I’ve always had his name on my racquet, and he’s the guy I play for. He got me into tennis, and I want to win for him as much as myself. We grew up in an area where winning was a big deal, and no matter what, we were competing. I still have that in my blood. It’s just part of my DNA.”

New Match

“You need an incredible amount of patience to win in tennis. You need to be mentally tough, obviously. Patience along with mental toughness is a big part of the formula for winning matches.”

Pop first applied for MAC membership back in 1982. He’d learned to bide his time on the court, which served him well in the years to come. He tried three more times before finally being accepted through the lottery in 2005.

In the meantime, he continued to refine his game with life and practice partner Patsy Bruggere, with whom he’s traveled the world over 34 years. “She’s an exceptional player and an even better person,” he says, giving her due credit for the role she’s played in helping him to stay sharp.

Popplewell recently returned from a rare solo trip to Antarctica, the last of the seven continents he had yet to visit. “I’ve been to 40 countries around the world,” he rattles off.

Statistics get Pop pumped. He’s caught 1,200 salmon and steelhead out of rivers in his life, and more than 20,000 fish total. He’s an avid fly fisherman, too, because of course he is.

“Being the sports junkie I am, I love everything MAC has to offer. It’s just a home away from home. It offers everything a true sportsman could love. MAC is like going into an ice cream shop with 31 flavors, except MAC has probably 100 flavors, and they’re all good!”

When Pop finally found his way into the promised land halfway through “the aughts,” he decided to make up for lost time.

Still Rallying

Over his tennis career, Popplewell has won 328 championship titles in singles, doubles or team events, and has been ranked No. 1 for his age group in doubles 25 times since 2000. But even just since the time he joined MAC, he’s won 11 gold, silver or bronze balls at Category I USTA National Championship events, and more than 30 Category II USTA National Championships. He was ranked No. 1 in USA Men’s 75 Doubles at the end of 2017.

He’s proud of these accomplishments, but never takes himself as seriously as the game. Ask Tennis Committee Chair Andrew Randles, Head Coach Paul Reber, or admirer Jim Lekas, and they’ll all tell you stories of both Pop’s bold competitive spirit and humble commitment to etiquette and sportsmanship. He’s never too busy to clean the green fuzz off the courts after a session with the ball machine, and he often takes time out to offer coaching to younger players still developing their games.

“I’ve always respected the game of tennis from A to Z,” Pop responds when presented with these details. That means a lifelong pursuit of self-improvement, and preferring defeat at the hands of a worthy competitor over lopsided triumph.

“You don’t have to look very far to find somebody that can whip you,” he points out. “I like to be tested. I’m always looking ahead to the next match. My main thing is just staying healthy and continuing to improve. I’m actually really looking forward to playing in the 85s division.”

“I still have, for my age, quickness, anticipation, and a long history of playing lots of matches and just staying in shape,” he says. “I'm thinking like a 30 year old and I should maybe think like a 78 year old. But I don't believe I'm really that old, you know?”

The Life and Times of Mas Kimball

Paul Fein

pfein@nsmta.net

September 2020

Mas playing singles in a local tournament at

Longfellow New Hampshire Tennis & Swim Club

When, where, and why did you start playing tennis?

It was in the early spring of 1978, during the heyday of tennis in the U.S., that a bunch of us living in the same building complex in Westchester, N.Y., which had two tennis courts, decided we would try our hand at this game called tennis. I read many books about tennis, of which The Inner Game of Tennis by Timothy Gallwey made the most impression on me. I suspect Mr. Gallwey's words spoke to me because of my upbringing as a Buddhist. To this day, I remember the phrase that hooked me ... “When the mind is free of any thought or judgment, it is still and acts like a mirror. Then and only then can we know things as they are.” That phrase has guided my tennis game since starting play at the age of 29 and all through my life.

What were your most prestigious singles, doubles, and mixed doubles titles?

In the eighties, I played tournaments on the American Tennis Association circuit. All the USTA tournaments in my area were held during the week, and I was busy getting my company started. So, my first exposure to USTA tennis was in the League program. Tournament singles and men’s doubles are a relatively new undertaking for me which I started playing in 2015. All the gold balls I have won come from playing the Husband & Wife Nationals, which I started playing in 2006 … 17 gold balls in all, with several silver and bronze balls also.

What was the name of your company? And what was the good or service your company provided?

Microware Systems began as a full-services computer company, which provided complete solutions to a client’s computerization needs—acquiring the hardware, software, training personnel, installation and configuration of the hardware and software, and writing custom software when needed. As the industry grew and matured, we got out of the hardware business, realizing the prices would be coming down and, therefore, the profit margins would get smaller and smaller. We concentrated on writing custom software for the garment industry in New York.

What was your biggest or most memorable win?

My most memorable singles match came in 2009 at an IC (The International Lawn Tennis Clubs) event in Moscow, at which I represented the IC of the Bahamas in singles and mixed doubles. In the singles, my opponent, Vladimir Molchanov, didn’t speak any English and my Russian was non-existent, but we managed to get through the few disputes without starting another Cold War!

Mas and doubles partner, Bill Drake, in Guilford, CT

After we split sets, a 10-point tiebreaker ensued to settle the match. After dashing out to a 9-3 lead and serving for the match, Vladimir faltered just enough to allow me to bring the tiebreaker to 9-9 and I eventually won 12-10. At the awards banquet, Vladimir presented me with a beautiful pewter mug and proclaimed, “War bad, tennis good.” We managed to have a wonderful conversation with two multilingual intermediaries at our table ... my English to French to Swiss to Russian, and Vladimir replying with reverse translations! This event truly exemplified what tennis means to me.

Please tell me more about the IC.

The International Lawn Tennis Clubs (IC), as one of its core values, plays matches between its 42 member nations among tennis players who have played representative tennis overseas. You can learn more about the organization at ictennis.net.

You wrote: “This event truly exemplified what tennis means to me.” What did this event truly exemplify to you?

Tennis, as with most sports, transcends politics, customs, language, etc. With the motto of “Hands across the net, friendship across the ocean”, the IC exemplifies and promotes all the ideas we strive for as human beings.

What have been the keys to your tournament accomplishments?

A willingness to always look to improve and to enjoy the experience rather than just to win. To improve, one must be in reasonably good shape, have a strong desire to continually learn new techniques and skills, and a willingness to be uncomfortable during this process. It is also beneficial to have one or more knowledgeable mentors to guide one through this process. I have been very fortunate to have several of these teachers.

Did your highly successful career in the computer industry help your tennis in any ways? And vice versa?

Not directly. Indeed, being focused, patient, and determined helped in both my career and my tennis. These are traits I would subscribe to my Buddhist upbringing.

Where were you born and raised?

I was born in Tokyo and spent most of my 7 years in Otsu, Japan, a small town outside of Kyoto. Three of those years were spent living in a Buddhist Monastery.

And what are the main tenets of Buddhism?

As with any guide to life, it isn't easy to distill a compendious philosophical practice to several basic tenets, so I will use the words of someone I admire and respect, Dr. Alexander Berzin:

Everyone wants to lead a happier life, but few know what that would mean or how to accomplish it.

Our emotions and attitudes affect how we feel. With training, we can rid ourselves of negative ones and develop healthier and more positive ones. Doing that will make our lives happier and more fulfilling.

Disturbing emotions such as anger, fear, greed and attachment make us lose peace of mind and self-control. With training, we can free ourselves from being under their control.

Acting compulsively out of anger or greed creates problems for us and leads to unhappiness. With training, we can learn to calm down, think clearly and act wisely.

Positive emotions such as love, compassion, patience and understanding help us remain calm, open and clear, and bring us more happiness. With training, we can learn to develop them.

Self-centered, selfish behavior and thought close us off from others and make us unhappy. With training, we can overcome them.

Realizing that we are all interconnected and that our survival depends on each other opens our hearts and minds, helps us develop concern for others, and brings us more happiness.

Most of what we perceive in ourselves and others are projections of fantasy, based on confusion. When we believe that our projections correspond to reality, we create problems for ourselves and others.

With correct understanding, we can rid ourselves of confusion and see reality. This enables us to deal calmly and wisely with whatever happens in life.

Working on ourselves to become a better person is a life-long challenge, but the most meaningful thing we can do with our lives.

What inspired you to collaborate with five other highly regarded seniors to found the National Senior Men’s Tennis Association in January 2018?

After I started to play USTA tournaments and then participate as a member of the USTA National Adult Competition Committee, it became evident to me that tournament participation was on a downhill trajectory.It was an uphill battle at USTA to foster some fundamental changes to improve the situation. The NSMTA seemed the perfect vehicle to address some of the problems, and perhaps influence the USTA to do the same. I am happy to say that our collective efforts, both with NSMTA and the USTA are beginning to bear fruit.

What statistics do you have to support your assertion that “tournament participation was on a downhill trajectory”?

Simply by looking at tournament player participation numbers over the past 10 years, there is no doubt that participation has been steadily decreasing.

Specifically, why was it “an uphill battle at USTA to foster some fundamental changes to improve the situation”?

In my opinion, organizations, like human beings, resist change. So, for many years, at the USTA, there was resistance to making sweeping changes. That being said, I think changes coming in 2021 is a huge step in the right direction and an indication of a significant shift in the administration of the many programs which the USTA supports.

Specifically, how have the collective efforts of NSMTA and the USTA begun to bear fruit?

NSMTA developed and fostered the flight round-robin format’s adoption, which guaranteed at least three matches for every player entering a tournament. The USTA and NSMTA have realized that an event is not just about tennis anymore, except perhaps for the top players. There needs to be more emphasis on the experience.

Through tournament sponsorships, the NSMTA has nurtured that idea by providing happy hours to give players more opportunities to socialize. The USTA will encourage tournament directors to provide a better experience with better support of TDs with a TD Handbook, improve communication with players, and better promote national tournaments, to name a few initiatives. CLICK HERE for a list of USTA 2021 changes.

I’ve talked to quite a few senior tournament players who have never heard of the NSMTA? What does the NSMTA do to ensure that every senior player is, at a minimum, aware of its existence—and if possible, aware of all it is doing to promote senior men’s tennis?

We continue to add new names to our email list. We encourage current members to talk with their friends who are not yet members. We have and will continue to run promotions for players who sign up multiple new members. We arrange to speak at any event’s player parties to promote the NSMTA. We hand out Information Cards at tournaments. Lastly, we are open to other ideas from all players to increase our membership.

What assets do you bring to the Board of Directors?

Having a background in IT, I started and maintained the NSMTA website, member communications, and e-commerce. When that job began to consume too many hours in my weekly schedule, the board hired my daughter, Keiko, to maintain it. My additional training in group dynamics and conflict management has helped navigate difficult issues that inevitably arise in any organization. My experience as a player and an organizer and tournament director of multiple local, national, and international events has allowed me to look at tennis from various perspectives. Lastly, as a member of the USTA National Adult Competition Committee, I have an avenue to introduce and discuss ideas about how to increase participation in Adult Age Group events.

Which issues do you plan to focus on? And why?

I would like to focus on increasing membership in the NSMTA. With more members, we will have a greater voice with USTA. It will also increase our budget to be able to do more for senior men's tennis.

You are the one of only 5 or 6 NSMTA members on the 17-member USTA Adult Competition committee, which has only 10 members who have played Senior or Super Senior men’s tournaments in the past four years. Put differently, we have very little representation on this powerful committee which makes very important decisions about Senior and Super Senior Tennis. Furthermore, this committee clearly lacks expertise and experience about Senior and Super Senior Tennis. What can and should the NSMTA do to rectify this serious problem?

Having nearly 60% of the committee who have played senior tournaments is, in my mind, quite good representation. There are also tournament directors, facility managers, tennis business owners, and event organizers that are part of the committee. I think the most important facet of this committee is the people's willingness to listen and carefully evaluate information presented by staff, other committee members, and the leadership. Therefore, I do not see it as a problem that the NSMTA need to address directly.

You serve on the USTA National Adult Competition Committee. What should the USTA do to advance the cause of senior and super senior tennis?

I think the information given above, addresses this question as well as the list of USTA 2021 changes noted above.

The initiatives that are currently being announced by the USTA for changes coming in 2021 are the culmination of many hours of hard work by a well-balanced group of players, tournament directors, facility managers and club owners. This brings together a diverse group of individuals with differing opinions but with one purpose in mind: to increase participation in the adult competition space. It is also led by a chairperson who has shown exceptional leadership and a staff person who understands our concerns and goes out of her way to help us meet our goals. The USTA is fortunate to have a combination of talent on this committee. All that being said, I think one of the most significant changes implemented is the removal of the Adult Tournament Rules and Regulations from the “Friend At Court” to stand alone as a separate set of Rules and Regulations, which can be amended by the Adult Competition Committee. This will allow changes to the rules, formats, requirements, etc., to be made expeditiously, giving the committee broad discretion to make necessary changes quickly.

Which national and sectional tournaments are run the best? What do they do especially well? And what can other tournaments learn from them?

They are too numerous to list. What stands out with all of them is that they provide a great player experience. Communication before, during and after the event is performed in a timely and respectful manner; most of them do a players’ dinner; match scheduling is done thoughtfully with very little delay times for players; the courts are in good shape; and every attempt is made to provide warmup courts.

Should every sectional tournament employ an accredited referee?

If you are referring to Sectional Championship-level tournaments, then yes, there should be a referee present. At other tournaments, this decision should be at the discretion of the tournament director and the Section.

On mixed doubles, the late humor columnist Art Buchwald wrote: “You either go to bed with someone or you play tennis with them. But don’t do both.” You and your wife Susan have won 17 USTA gold balls in husband-and-wife doubles. How have you managed to disprove Buchwald’s dictum?

How about the dictum, “Never go to bed angry” translated to the tennis court, “Never step on to the court angry.” We had our moments when we didn’t heed that advice, but for the vast majority of the time, we were successful following that adage. We agreed that I was the captain on the court, and as a good captain, I would always elicit the advice of my partner. We would discuss strategy during changeovers and review matches at their conclusion, especially if we lost. On the court, I looked at Susan not as my wife but as an excellent partner with whom I had the privilege to play. Full disclosure: Although Susan and I are no longer married, it was not a result of our experience on the court.

You’ve worked as an organizational administrator in local, state, federal, and presidential elections. Which politicians have you helped during their campaigns, and how did they fare? And which causes are you most passionate about?

Over the many years I have been involved in politics, I have worked with Democratic, Republican, and Independent campaigns. Some won, some lost. During the same period, I have been involved in many activism causes. I cut my teeth on the Civil Rights movement and later on the Vietnam antiwar movement. My latest involvement has been with Climate Change.

You’ve helped organize and run several tennis clubs, numerous tennis tournaments, and many regional and international tennis events. Would you please tell me about your service in these areas.

I took up tennis late in life during the heyday of tennis in the U.S. when there was great interest by newly engaged players to play, improve, and get together for tennis social activities. Along with half a dozen others, I formed the Westchester Plaza Racquet Club, named after the housing complex where we all lived in Mount Vernon, N.Y. We created a monthly newsletter, held tournaments, and organized tennis outings during the summer and indoor tennis parties in the winter. Before long, we had more than 270 members from all over Westchester, from four of the five boroughs of New York City and from Long Island.

Given my computer experience, I also helped several tennis clubs in Westchester streamline their operations. Back in those days, there were no software programs for tennis clubs, so I set out writing and implementing these programs. I lead the WPRC as president for five years, but as my interest in tennis organizing broadened, I had the opportunity to travel internationally. I volunteered my services for several organizations. Two that come to mind are the I.C. of the Bahamas (of which I am a member) and the Peter Phillips Tennis Club, formerly The Brandon Cup Championships, which was an outgrowth of the Davis Cup selection process for the West Indies. That would be an interesting read of what that was all about but for another time! For each of these, my computer and tournament director skills allowed me to contribute to the continued success of these organizations.

What do you believe are the NSMTA’s most important accomplishments so far? And why?

For a young organization, we have accomplished quite a bit, but several accomplishments stand out. First, the introduction of the Flight Doubles format. This format has afforded more play for what I call the Tier 2 and Tier 3 players—those who typically do not reach the quarterfinals. The format strives to guarantee a minimum of three matches per team, making for a better player experience. This format has been adopted by the USTA and will be used for all national doubles events.

Another aspect of tournaments often ignored is fostering camaraderie amongst the players. The NSMTA now sponsors a happy-hour towards the end of the day at a number of tournaments. We feel this also enhances the player experience.

Third, the relationship that the NSMTA has forged with the USTA has been very beneficial to both organizations. It was a bit of a tightrope in the beginning with players concerned with us just being a mouthpiece for the USTA. At the same time, the USTA voiced concern that we were going to work against the USTA and perhaps start an adversarial organization. I think we have managed to show all the concerned parties that we are an independent, well-run, knowledgeable tennis association with the best interests of senior men’s tennis as our foremost concern, and that we can influence the USTA in positive ways.

The Many Loves of Hugh Burris

Ed Trost

etrost@gmail.com

September 2020

NSMTA Member, Hugh Burris

As the son of a Navy aviator, Hugh was a self-described “service brat”, having called several places “home” during his childhood years. This constant movement amongst houses helps prepare one to become independent and comfortable with different and unknown circumstances and experiences.

Hugh’s Dad loved to fish and so, at three and a half years of age, he would tag along with his Dad, and this began a life-long love affair with fishing. His independent streak served him well in fishing when Hugh became a “commercial” fisherman at the age of ten. He would take his boat out on Chesapeake Bay, MD (where his Dad was stationed at the time), catch a few dozen crabs daily and sell them to a broker for $2 a dozen. Not too shabby for a kid his age.

Hugh’s family finally settled in Kingsville, TX, where he played basketball in high school with hopes of getting a scholarship to college. Although his basketball dreams did not come to fruition, he became a pre-med major at Texas A&I (now Texas A&M – Kingsville), graduating in three years and then to medical school, and his internship and residency at UTMB (University of Texas Medical Branch) – Galveston. During his internship on Christmas day 1972, his first day in the emergency room, he felt like he “died and went to heaven.” He had found his calling as an ER doctor, which has been his professional endeavor over the past 45 years. Reflecting on what it is about the emergency room that makes his bell ring, Hugh says, “It’s about the detail, it’s about the unknown of what’s going to walk in through those doors. Whether it’s a sprained ankle or a heart attack, the ER doctor must be prepared for anything and make decisions quickly and decisively”. That is what makes the job exciting, and his upbringing helped prepare him for those unknown situations he faces every day.

Hugh did not start playing tennis seriously until after completing his residency at the age of 28. He started playing national tournaments at 35, and has played at least one or two nationals a year ever since. Although Hugh plays left-handed, he wasn’t born so. Hugh’s Dad had aspirations for him as a southpaw in baseball. In fact, his Dad was so intent that he become a lefty that when he was three years old, Dad would tie Hugh’s right hand behind his back so he would be forced to throw left-handed (something Hugh found out later in life from his Dad).

Although he has never won a gold ball, he has a few silver balls to his credit in both singles and doubles. His silvers in singles are among his greatest tennis moments as he lost in the finals to two great senior players, Brian Cheney and David Nash. He has also won a bronze ball with his daughter Liz (who played college tennis at SMU and is currently a teaching pro in the Houston area) in the Father-Daughter Nationals. He also plays the Husband-Wife Nationals with his wife of 34 years, Carol.

As one might imagine, being an ER doctor can be extremely stress-provoking. For Hugh, tennis offers a relaxing outlet from a stressful job and maintains his physical fitness and mental well-being. Observing the ever-present fragility of life in his work, he fully appreciates every day what life offers him. As a result, he’s able to put winning and losing in tennis into perspective. Tennis has also given Hugh tremendous joy in the life-long friendships he has made, even more than he made in all his years in medicine. These friendships have probably more than made up for the ones he may not have had as a young boy always on the move.

As much as Hugh loves tennis, it seems that it takes a backseat to his love of Carol and fishing, in that order! When asked what he loves about fishing, his reply is quick and succinct - “Everything!”. From catching and selecting the proper bait, to learning the water and the fish’s tendencies, to the wonders of what wildlife you might see, (sea otters, turtles, etc), fishing is one more way of escaping the hectic life of an ER room. That he can fish and play tennis nearly every day tells you that Hugh truly has his life in balance, something for which we can all strive.

Leland Housman: Cardiovascular Surgeon & Senior Tennis Champ

Ed Trost

etrost@gmail.com

August 2020

NSMTA Member Leland Housman

To have learned your craft from world-class teachers is an awesome gift. At the same time, it’s incumbent on you to embrace the challenge of living up to expectations those teachers may place on you as well as those expectations you place on yourself. The dedication to the craft requires focus, time and effort. When your craft involves life and death consequences, the focus and commitment become even more paramount and intense. Such was the case with senior tennis champion Leland Housman who became one of the nation’s leading cardiovascular surgeons over the 40 years of his practice in San Diego.

Leland graduated from the University of Texas-El Paso (UTEP) in just 2 ½ years by taking classes year-round. He knew after watching a fellow tennis player who also happened to be a vascular surgeon perform surgery, what his medical future would look like. He attended the Baylor School of Medicine for 4 years as a student and one year as an intern primarily because of Dr. Michael DeBakey. Baylor was at the forefront of cardiovascular surgery at the time, and DeBakey was its most prominent doctor. For those unfamiliar with the DeBakey name, it would be safe to say that he was the most well-known cardiovascular surgeon in the country, if not the world. He pioneered procedures that are now commonplace, such as bypass surgery, as well as inventing several devices designed to help heart patients. DeBakey took a liking to Leland, especially when Leland expressed interest in becoming a surgeon. Leland describes DeBakey as a taskmaster and someone who could be quite intimidating. Leland vividly recalls DeBakey dressing down a resident when he was not quite on his game by saying, ”Your lack of attention to detail is amazing!”

After his internship at Baylor, DeBakey encouraged Leland to do his residency at the University of California, San Diego, where the top cardiologist in the country and the head of the NIH Cardiology Section, Dr. Eugene Braunwald, was heading up the cardiology program at UCSD. Leland spent his residency at UCSD and studied under the first woman to be certified by the American Board of Thoracic Surgery, Dr. Nina Starr Braunwald. She was a pioneer in cardiac surgery in her own right, having designed and developed many of the early artificial mitral valve prostheses.

When his five years of General Surgery residency were up in San Diego, fewer than a handful of medical schools allowed residents to perform significant numbers of cardiac surgery under supervision. So Dr. Starr-Braunwald recommended that Leland attend one of those schools, the University of Oregon, where he did his Cardiac and Pulmonary Surgical Fellowship for two years.

Once he completed his fellowship in Oregon, he and his future wife, Carolyn, headed back to San Diego where he would have an opportunity to practice surgery and re-engage with the sport he loved. A requirement of their first home was that it have a tennis court. That home, which initially sported a hard court and since converted in 1999 to a Har-Tru clay court, is still where he plays most of his tennis. When asked if he ever has a problem finding an opponent, he replies, “there’s no shortage of players who want to come over here and beat me.”