Let's do great things for men’s tennis, together!

Slices from the Past

Periodically, we will post a "blast from the past". Magazine articles, newspaper clippings, stories, videos, etc. That we think may be of interest to our readers. Do you have a topic from the past or article in which you think other members would be interested in? Email our editor!

If you would like to contact the author, please click on their email address.

Life on the Men’s Tennis Circuit

Video by: Roger Dowdeswell

rrogerd1@aol.com

Video Intro: Jimmy Parker

prkrtennis@aol.com

December 2020

You are about to enter a time capsule when you set out to watch this fascinating 20 minute film made by NSMTA member Roger Dowdeswell over 40 years ago. In it, he interviews players on the ATP Tour, both well-known and not. He is interested in getting their feeling about life on the tour, (and off as well). It was especially interesting to me because I recognized most of the players, and would be interested in finding out what their lives have been about during the succeeding four decades! I suspect that many of their revelations would be equally true today if one were to interview modern tour players - journeymen and stars.

The Club Where It Happened:

Notes on the Origins of USTA Men’s 55+ National Tournaments

Chuck Maland

cmaland@utk.edu

June 2020

Despite the cancellations of many national senior men’s tennis tournaments this year—a pandemic year we’re unlikely to forget—we are enjoying a Golden Age of senior men’s tennis. The formation of the National Senior Men’s Tennis Association is just one indication of that fact. Even more significantly, the USTA now sanctions national tournaments in singles and doubles on all four surfaces—indoor hard court, hard court, clay, and grass—in every 5-year age group between the 55s and the 90s.

Yet it wasn’t always so. According to USTA history, this is when the first USTA national men’s tournaments in different age groups were staged:

90s — 1999

85s — 1983 (but then not held again until 1988)

80s — 1977

75s — 1973

70s — 1970

65s — 1968

60s — 1966

In many cases—though not all—just one national tournament was held in the first year in each of these age groups, usually on clay, followed by the next year when competitions in all other surfaces joined in. The USTA website lists the singles and doubles champions of all these tournaments here. (Unfortunately, you won’t find my name there, but you will likely recognize a lot of names, perhaps even yours. If my legs hold up, though, I’m going to keep trying.)

Not enough people know, however, that the first USTA 55+ National Men’s Tennis Tournament was hosted at the club where I most often play, the Knoxville Racquet Club. Here I’d like to offer a brief history of that first tournament and a few observations about how that tournament, despite many differences, is similar to many of the national tournaments that we play today.

For those who don’t know the geography of East Tennessee, Knoxville is nestled in the foothills of the Great Smokey Mountains. Interstate Highways 40, 75, and 81 converge and go through the city; thus we’re within several hours’ drive of Lexington Ky., Asheville, N.C., Atlanta, and Nashville. It’s the home of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the University of Tennessee (where I’ve taught cinema studies and American literature for 42 years), and the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. The corporate headquarters of Regal Cinema and Pilot Oil are in Knoxville—Pilot’s corporate offices are a stone’s throw from the Knoxville Racquet Club—and several video production companies, including Discovery, are active in Knoxville, partly because of lower production costs than in New York, Los Angeles, and Atlanta.

The Knoxville Racquet Club was then a recently established, member-owned club, having been founded in 1961. When the tournament was held in 1963, the club had 11 clay courts and some indoor hard courts: today, besides 12 clay courts, we have five outdoor hard courts and ten indoor hard courts. The clubhouse sits atop a Tennessee ridge—players have to drive two-tenths of a mile up a steep asphalt road off Lonas Drive to get to the parking lot. The courts were built on two separate tiers below the clubhouse, so anyone interested in watching matches can sit at the top of one of those tiers to watch competitions, which may have been one draw to hold the tournament there. Players walk down 18 steps from the clubhouse to play on the first tier of courts; the second tier goes down even farther.

Knoxville Racquet Club Clubhouse today

The view overlooking the top tier of courts

The groundbreaking tournament was held October 15-21, 1963. To anchor this in history, it was two months after the historic March on Washington, when Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream Speech,” slightly more than a month before John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, and about four months before the Beatles first performed on the Ed Sullivan Show.

However, the tournament was by no means the only big event in Knoxville that week. The Hollywood movie adaptation of James Agee’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel, A Death in the Family—retitled All the Way Home—had its world premiere at the Tennessee Theater, with star Robert Preston and producer David Susskind attending. (Agee grew up in Knoxville, and the semi-autobiographical novel is set in Knoxville in 1915.) The University of Tennessee football team was preparing for a road game in Tuscaloosa: the Saturday of the tournament semifinals the Crimson Tide crushed the Volunteers, 35-0. National Senior Men’s Clay Tournaments continued in Knoxville through 2004, but the tournament was always held in September or October on an open date or an away game for the Tennessee football team. (It kept hotel prices down for tennis players—home football weekends swelled Knoxville’s population and hotel rates!)

Both of Knoxville’s newspapers—the morning Journal and the afternoon News-Sentinel—gave daily coverage to the tournament. Roe Campbell was the chairman of the tournament committee. He and two other Knoxvillians—69-year-old Ebb King (the oldest entrant) and Dr. Alex Shipley—were entered, and the field also included Dr. Milton Bush from Nashville (one-time coach of the Vanderbilt University men’s tennis team) and Eldon Roark, Sr., a syndicated newspaper columnist at the Memphis Press-Scimitar. I’ll come back to Roark later. But it was an impressively national field for the first such tournament: it included players from California, Oregon, Texas, Oklahoma, Florida, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Minnesota, among other states.

Tournament play began on Tuesday the 15th. The singles draw had 52 players: 20 matches were played on the first day. The seeding worked differently at this tournament because all five seeds played the first day, while six more first-round matches were played on Wednesday. The seeds included: 1) Joseph Lipshutz from Philadelphia (who had been a four-letter athlete at Temple University and a high-school high jump champion); 2) Monte Ganger of Cleveland; 3) William Roeder of St. Louis; 4) Dave Freeborn of Tulsa; and 5) James Hodgkins from Santa Barbara. All won their opening rounds: Freeborn’s 6-3, 6-2 victory over Henry Rupp from Huntsville, Alabama, was the tightest of these five matches. (Alas, all the Knoxville entrants lost the first day.)

Henry Rupp can’t quite run down a forehand Joseph Lipshutz (left) | Dr. Milton Bush checks the second-day draw (right)

Photos from News-Sentinel, October 17, 1963

As in most of our national tournaments today, doubles and consolation play began the second day of the tournament. Three doubles teams were seeded: 1) Ed Leonard (a former NFL player) and James Hodgkins; 2) Joseph Lipshutz and Bernard Clinton; 3) William Roeder and Dave Freeborn.

The tournament started heating up and the seeds started falling on Thursday and Friday. Bernard Clinton, from Dallas, upset the third-seeded Roeder on Thursday, then knocked off the five-seed Hodgkins 6-3, 7-5. Dr. Milton Bush from Nashville, who was born with only one arm, rallied from deficits in both sets against fourth-seeded Freeborn, winning 7-5, 6-4 to reach the quarterfinals.

Top-seed Lipshutz told News-Sentinel reporter Bill Luther on Thursday that “there are seven players still in the singles that could take the title.” Noting that many of the players had been nationally ranked in their younger years, Lipshutz added that “a lot of college players would envy the way that some of them hit the ball although some are approaching 70.”

On Saturday Lipshutz finished Dr. Ford’s run with a 6-4, 6-1 semifinal victory, while his doubles partner Bernard Clinton upset his third-seeded player in as many days, knocking off second seed Monte Ganger, 6-4, 6-4. In doubles, all three seeded teams made it to the semi-finals. Top seeds Leonard and Hodgkins, from Portland, Oregon, won their semi-final match, defeating the third seeds Roeder and Freeborn. Unseeded Lyle McCannon and Monte Ganger were down a break, 1-3, in the first set against second-seeded Lipshutz and Clinton, but they rallied to a 6-3, 6-2 win.

Lipshutz and Clinton pose before their singles final

News-Sentinel, October 20, 1963

The singles final on Sunday was a hard-fought match. Lipshutz got an early break and was up 3-0 and later 5-2, but Clinton won four straight to go ahead 6-5 and eventually won the set 9-7. In the second, Clinton got an early break to go up 3-1 and held the break to win the second set 6-3 for the coveted title. Following the match, the gracious Lipshutz told reporter Bill Luther that “Clinton is a mighty fine tennis player, and he didn’t seem to tire as much as I thought he would.” Clinton admitted to Luther that Lipshutz “really put the pressure on me. It looked pretty bad when he took the first three games of the opening set.”

The doubles finals generated at least as much excitement. Hodgkins and Leonard won the first set 6-3, lost the second to McCannon and Ganger, 7-5, and were tied at 7-7 in the third when the match was stopped because of darkness. Forced to return to finish the match on Monday morning, McCannon and Ganger got a hold and a break to win 9-7 in the third. So in the first national men’s 55+ tournament, unseeded players took home the victory trophy in both singles and doubles. (In addition, Clinton was 59 when he won the tournament: today he would have been in his last year of the 55s division.)

The day after the tournament ended, both daily newspapers in Knoxville congratulated the tournament committee and the club for a job well done, and 2nd-place singles finisher Lipshutz seemed to speak for the participants by complimenting the setting, the organization of the tournament and the people, adding that the tournament “was a nice as any I’ve ever played in.”

* * * * * * * * *

As I look back nearly 58 years, I can note significant differences between this tournament and the ones we’re playing today: the players all seemed to be in tennis whites (at least the ones who made it into newspaper photos). All the players used a wooden racquet, and none of those racquets had a head that approached 120 square inches; in fact, they all were 65 to 68 square inches. There were no third-set super tiebreakers. In fact, there were no tiebreakers at all, as witnessed by the 9-7 scores in the first set of the singles finals and the last set of the doubles final.

But there were similarities, too. Aches and pains were clearly there, as they are in our day: three of the opening day matches were decided by default. The camaraderie that we see in many of our tournaments today was evident in this first tournament in Knoxville. Some of the players were familiar with one another from matches in the past, good evidence of their continuing passion for the game.

There was also a good bit of storytelling by players not on the court. I had to laugh at one comment by an unnamed player who told a Journal reporter: “The old tennis balls had more rubber in them than these modern ones—I remember 1927 as a year when they really took off when you hit ‘em.”

Senior tennis really began to take off after the inaugural 55+ tournament in Knoxville. By the end of the decade, Knoxville was hosting four national senior men’s clay age-group tournaments: the 55s and 60s at the Knoxville Racquet Club and the 50s and 65s at Cherokee Country Club. Multiple USTA Senior Champions like Bobby Riggs and Gardnar Mulloy became fixtures in the tournaments starting in the late 1960s. Later, the 55s and 65s continued to be a staple in Knoxville, though to my great disappointment—I couldn’t travel to national tournaments because of my job—the 55s moved to Atlanta in 2005, the year after I turned 55.

I hope this has been an informative history lesson about the first national USTA men’s 55+ tennis tournament. I’ll close with a comment by Eldon Roark Sr., an award-winning columnist from the Memphis Press-Scimitar who won a couple of singles matches in the consolations in this 1963 event. Early in the week, he told a News-Sentinel reporter that tennis was a “profitable” game for him, then explained at some length, in words that I think many of us can appreciate:

“Tennis really paid off for me. I haven’t paid any money to doctors or missed more than two or three days of work in thirty years. Tennis is a game for a lifetime. There are men at this tournament up to 69 years old who still play remarkable tennis—and believe me, it takes co-ordination, stamina, and grace to play tennis.

A quick glance around these courts backs me up. There aren’t any fat men here. Tennis helps to burn up calories and keep men quick on their feet. Many of these men have been playing tennis for over 50 years. This is serious tennis for these men. They really mean business. You’ll find keener competition among these seniors than in any other division.”

USTA Plaque commemorating the 1963 tournament at the club where it happened

As we look forward to the resumption of our senior age-group tournaments, it’s useful to look back to see earlier evidence of the same passion and appreciation for tennis that many of us share. Before you leave, see the plaque (left), placed by the USTA in 1982 at KRC.

* * * * * * * * *

Chuck Maland is a Professor Emeritus and former Head of the English Department and Chair of Cinema Studies at the University of Tennessee. Besides playing as much tennis as he can, he’s author of a number of books on American movies, including Chaplin and American Culture, and he most recently edited a volume that includes all of James Agee’s movie reviews and criticism: Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, Manuscripts. Thanks to Paul Fein for his careful reading of the essay and some good suggestions.

Davis Cup - Now And Then

Mark Winters

mwinters@nsmta.net

November 2019

1963 Davis Cup Team-Arthur Ashe, Dennis Ralston, Robert Kelleher, Marty Riessen and Chuck McKinley

Photo: Robert Kelleher Collection

Now that the “bigger must surely be better” version of the Davis Cup has concluded, it’s time to take a look at how the event itself has evolved over time. Initially, it was a clubby/chummy affair between the US and the British Isles, as Great Britain was known long before there was even a thought of Brexit. True, there had been international, country versus country tennis gatherings, such as England versus Ireland or England versus France, but that was in the 1890s. The “official” team competition wasn’t birthed until 1900 when the US and BI faced-off at Longwood Cricket Club in Boston, Massachusetts.

The visitors, who were supposed to be the creme de la crème of tennis because they came from Great Britain, were throttled by their upstart hosts, 3-0. One of the competitors on the winning side was a Harvard student named Dwight Davis. Five years after the launch, Australasia (with players from both Australia and New Zealand), Austria, Belgium and France took part in what was called the International Lawn Tennis Challenge. Perhaps to downplay the seeming pompousness of the title, the competition quickly became known as the Davis Cup, a salute to the donor of the perpetual trophy.

In the beginning, the competition was played as a Challenge Cup. The set-up allowed the winner from the previous year to sit on the sideline while the other countries battled for a spot in the final. The “wait and watch” was great for the title holder but the format proved to be an ultra-marathon for all the other participants. In 1972 a change was finally made, and play became a somewhat more sensible win and advance tournament.

Since then, the international competition grew so large that it became unwieldy and modifications were needed. None of those alterations have even come close to matching the November 18-24 Madrid extravaganza that was created by Gerard Pique, the former FC Barcelona football (soccer) star and his Kosmos team, supported by Hiroshi Mikitani’s Rakuten financing and sanctified by the International Tennis Federation.

Before going further, it must be stressed that the “old Davis Cup way” was really no longer working. But, bulldozing history to put up a new event demands an overwhelming amount of thought and even more insight. Thus far, it appears that a “too much, too soon” approach has been built on a foundation that isn’t exactly sand, but something nearly as tenuous. In its first appearance, the set-up seems fragile. It is as if, Pique and his colleagues were trying to create a Tennis World Cup.

My first Davis Cup experience was in 1963 at the majestic Los Angeles Tennis Club. The US faced Mexico. I was new to the game as a player and even more of a rookie when it came to knowing about the Davis Cup. Being in high school, I didn’t have the necessary connections to be “gifted” a ticket to the matches. Though I wasn’t destitute, I just didn’t have the money for tickets to the three-day tie.

I was, however, bold. I wanted to see Chuck McKinley and Dennis Ralston take on Rafael Osuna and Antonio Palafox so I decided to “make an impression.” I wore a pale blue shirt, topped it with a tasteful tie, preppy khaki slacks and the footwear of the day – that wasn’t a tennis shoe – penny loafers. Carrying my blue blazer in the crook of my elbow, I arrived very early on the first day of the matches and went directly to the fence at the back of the LATC where the wire was sagging just enough to let me scale over.

Even though I was a Davis Cup novice, I remember being impressed by the sheer dynamic of the US facing off against Mexico. The backstory was even more interesting because as a 17-year-old Ralston had teamed with Osuna to win the 1960 Wimbledon doubles title. Now, Osuna was his opponent, but he was still a USC teammate. Together, they had practiced at the LATC , where USC played its home matches, and coincidently, won the 1963 NCAA doubles title. But, that didn’t matter at all for the three days of the tie.

The LATC center court seemed gigantic to me. As mentioned I was a rookie and this was my first glimpse of play on a big stage. The bleacher seating was on wooden benches surrounding the court. There was room for a couple of thousand people. Because I was so early, there were very few people around. I browsed around and noticed there were individual chairs at court-level on the west side of the court. They looked much more comfortable than the bleachers and my goal was to be close to the action. I wanted to taste it.

After all these years, I can still remember being a tad uncomfortable making my next move. But I figured after my Eiger Mountain entrance success, I managed to continue with my “I belong here” approach. After putting on my sport coat, I walked onto the court and went straight to the seating area…and was one of the few spectators there. In time others joined me. I exchanged greetings, trying to be friendly while attempting to be invisible. Just before the start of play, a small man, who was importantly dressed, came up and started to talk to me. For a moment, I almost swallowed my tongue.

He was John Coman, who I later discovered was a Southern California Tennis Association Vice President and a close friend of Perry Jones, who was the “Emperor of Tennis” in the section. During our brief discussion, he told me about his love of the game and his long-time involvement as a tournament official and umpire. (In fact, he would later invent the Coman Tiebreak, which Jimmy Parker said some senior players refer to as “The Roamin’ Coman”).

When the matches concluded, I bumped into Coman on the walkway outside the court entrance. He asked what I thought about the first day’s play. After we exchanged assessment, he asked if he would see me the next day. Believing that Friday had been a “one-off, I really lucked out” occurrence, I was eventually able to mumble “I hope so…” He then said when I got to the club to look for him at the SCTA office, which was in a nook on the east side of center court.

For the next two days, I repeated my back fence climbing routine, watched the US dominate Mexico, 4-1 and received a wonderful tennis education thanks to John Coman.

(An important aside, the US went on to defeat Australia in the December 26-28 final, on grass in Adelaide, 3-2. The Honorable Robert Kelleher, who I met through Coman at the LATC, was the team captain. He served as President of the United States Lawn Tennis Association in 1967-68 and was a driving force behind the advent of Open Tennis. The International Tennis Hall of Fame recognized all that he had done for the game when he was inducted in 2000. A Federal Court Judge in real life, over the years, he provided tennis players like Jack Kramer, Richard “Pancho” Gonzalez, Arthur Ashe and Billie Jean King with legal advice. He also played an instrumental role in Martina Navratilova’s gaining US citizenship after she defected from Czechoslovakia in 1975. In the years after our Davis Cup meeting, “The Judge” became a close friend.)

The Madrid undertaking was bold and innovative. Still, with all the pre-tournament hype and sensationalism as fanfare, the end product came up short which opens the door to analyzing what actually took place in Year One. As the saying goes, “first impressions are almost always the most lasting.”

A few of the issues on the “Could Have Done Better” list include:

Match scheduling (the US versus Italy finished at 4:00 a.m., just in time for the players to enjoy an early breakfast. (Nearly every match was almost nine hours in length.);

Plodding ticket sales;

Improvements in communication, with clarity for the fans, players and media. Keeping accurate information flowing so that speculation is not regularly brought into play.

With the old Davis Cup there were often gripping, edge of your seat, emotional contests in the “five matches, five-set” play. Home and away ties added crowd fervor which made the competitive recipe even tastier.

It’s hardly surprising that whenever Spain played on the Manuel Santana Center Court, with a capacity of 12,422, the crowd was raucous. The Arantxa Sánchez Vicario No. 2 Court, with room for 2,923 spectators, rocked on occasion. From time to time, Court No. 3 was loud too, but that was due more to having a mere 1,772 seats in an enclosed space than a collection of rabid fans.

Australian captain Lleyton Hewitt admitted that the atmosphere lacked feeling because of the neutral setting. French doubles standout Nicolas Mahut brought up how much his country’s fans ordinarily helped their team, but few were in attendance. Faithful support groups stayed away to show their unhappiness with the decision to scrap the old Davis Cup format.

US Davis Cup Team Doctor, George Fareed and Mark Winters on court at Palais des Sports Gerland.

I clearly understood what Mahut was talking about. I had been in Lyon in 1991 when the US faced France, on carpet, in the final. The atmosphere at Palais des Sports Gerland was electric, truly vibrant. The hosts were the underdog against US captain Tom Gorman’s team, which included Andre Agassi, the formidable doubles tandem, Ken Flach and Robert Seguso, and a 20-year-old making his cup debut, Pete Sampras. Les Bleus had not won the treasured trophy in 59 years. Prior to the tie, it seemed they could only hope for a three-day “Joan of Arc” moment.

The revered Yannick Noah, the last Frenchman to win Roland Garros in 1983, had retired from competition in 1990. He was in his first year as Davis Cup captain. Though Guy Forget, who is now the Roland Garros Tournament Director, was solid, he was not in the same league as Agassi and Sampras. What’s was more, Noah was desperate to find a second singles player. He reached into his “magic bag” and selected Henri Leconte.

Leconte was the poster boy for left-handers playing the game on the elite level. In essence, he could be wickedly brilliant and pedestrianly laggardly all within an eight-shot rally sequence. Ranked No. 143, after dealing with a collection of injuries that ravaged both his body and his confidence, he was an extremely risky choice. The final member of the team was Fabrice Santoro, a two-hand playing, shot-making magician. He had played in earlier rounds, but this was the final and he was only18.

Thinking back, my ears begin to ache as I recall the deafening support provided by the crowd of over 7,000. Initially, Forget was inspired and took the first set, 7-6 against Agassi. Thriving in combustible surroundings was nothing new for the American. He became more precise marching through the remaining sets 6-2, 6-1, 6-2. Leconte balanced the score edging a nervous Sampras, 6-4, 7-5, 6-4.

Flach and Seguso were never spectacular as a team, but they were reliably steady. Against Forget and Leconte, they appeared to by trying to escape the Titanic. The 6-1, 6-4, 4-6, 6-2 score reflected how unsuccessful they were at reaching the lifeboats.

Sampras was first up on Day Three and again seemed to be very tight. Forget took full advantage and secured a 7-6 3-6 6-3 6-4 victory. In was his country’s first Davis Cup final triumph since 1932 when the US also came up short. During the celebration, Forget said that he didn’t think the US team understood how much the Davis Cup meant to the French team and to the partisan crowd.

Years after the tie, Sampras admitted being overwhelmed by the crowd and reacting like a “deer in the headlights.” (He candidly said, “I choked…”)

1995 Davis Cup Team-Richey Reneberg, Jim Courier, Andre Agassi, Tom Gullickson, Pete Sampras and Todd Martin Photo worldtennismagazine.com

Four years later he didn’t “choke” against the Russians. For me, being in the early December dungeon cold at Moscow’s Olympic Stadium in 1995 and watching the US prevail 3-2, post-Cold War, against “new” Russia is a cherished recollection.

Captain Tom Gullickson was, as always, a discerning leader. Of course, he had a redoubtable group of players including Sampras, Jim Courier, Todd Martin and Richey Reneberg, who was a late replacement for the injured Agassi. The Russians had countered with Andrei Chesnokov, Yevgeny Kafelnikov and doubles specialist, Andrei Olhovskiy.

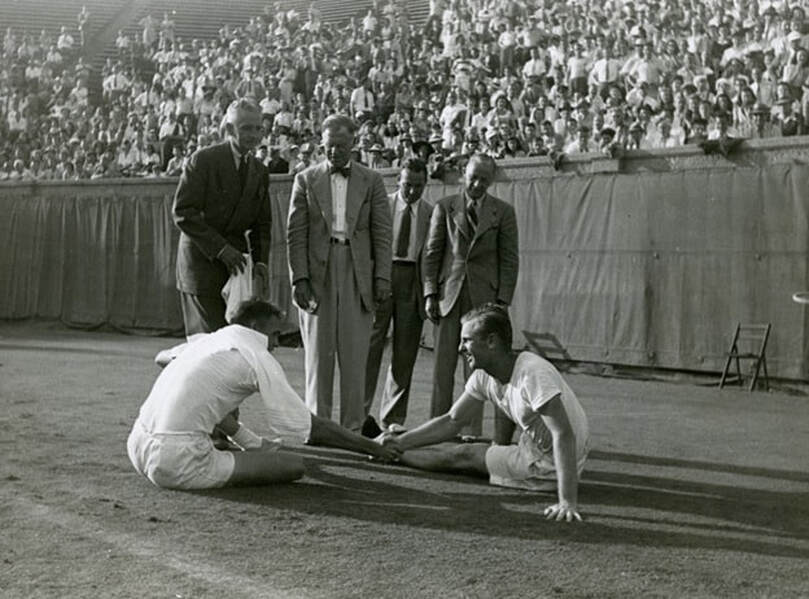

In what some called “Pete’s Cup”, Sampras, in a difficult to put into words encounter, survived a three-hour, thirty-eight minute slog against Chesnokov, 6-3, 4-6, 3-6, 7-6, 6-4 on ultra-slow red clay. The score, in and of itself, is still mesmerizing. But, seeing Sampras hit the match winning shot and collapse onto the court with severe leg cramps will always be a vivid memory.

As soon as he crumpled to the ground, George Fareed, the US team doctor, along with trainer Bob Russo sprinted to his aide knocking over some of the shrubbery surrounding the court. Sampras later admitted that it was humorous to see the two barreling toward him while he was thinking “all I want to do is straighten my legs.”

Once the medical rescue team and the patient moved to the locker room, Kafelnikov bested Courier, in the second, contest, 7-6, 7-5, 6-5.

Being 1-1 and playing at home with the backing of a vociferous crowd, the Russians appeared to be in the driver’s seat. This was particularly true with the doubles being the next match up. Kafelnikov was paired with Olhovskiy. A steady, smart tandem, they were supposed to face Martin and Reneberg, who had never previously teamed up.

Keeping with the “Pete’s Cup” theme (and thanks to “Doc” Fareed’s icing and electrolytes treatment), Sampras was able to wobble around in the team dressing room roughly an hour after his singles match. He told Gullickson later that night he would see how he was feeling in the morning and if he was able to do so, have a hit and be ready for the doubles.

The team believed that Sampras was out, but as the captain said, with a “that’s Pete” look, “he came back from the dead”. Sampras admitted being quite sore before play began. Then the adrenaline kicked in. Martin and Sampras, who had won Queen’s that June, managed to edge the opposition, 7-5, 6-4, 6-3.

I remember watching the match as if it was in slow motion. It overwhelmed my attention. Looking back, I don’t remember if I ever took a sip of the water I had brought with me to my media seat. I was absolutely engrossed. Actually, I was enthralled watching Sampras playing and doing it so amazingly well.

But, he wasn’t done. On the final day, he pulverized Kafelnikov, 6-2, 6-4, 7-6 to end the tie. Courier lost, what was an exhibition match, 6-7, 7-5, 6-0 to Chesnokov making the score 3-2. But, the real total was Pete Sampras, with an assist from George Fareed and Bob Russo, “3” and Russia “0”.

It is something I will never forget. Actually, I don’t think that anyone on hand could ever forget what unfolded during those three days.

In Madrid, ties were reduced to three matches (two singles and just one doubles) which made the contests Tweet-like. Instead of slashing the number of characters that could be used, the new look limited the essence of the product being proffered – Showcasing the players and their teams. The confusion became more profound on the rules front when it came to “play or don’t play” the doubles, the tie-break and translating the results procedure. It seemed only those with a mathematics degree could make sense of the situation. Additionally, with 18 countries participating, many fans, as well as players, ended up feeling they were meandering members of a “lost tennis tribe.”

Because of the venue’s layout, there was a chorus of comments about the need for trekking skills to traverse the architecturally pleasing Caja Mágica three court facility. Pathways and route planning came up short. Perhaps hosting such a huge spectacle at a new location brought about “never been there or done it” first experience jitters.

Looking at the big picture, the most staggering aspect of the “new” Davis Cup has to be the 25-year agreement with $3 billion dollars at stake. How do tennis fans put these “Monopoly-money” like figurers into any meaningful perspective?

The quarter-century commitment and pledged funding are difficult to comprehend . The “unreal” combination of years and money brings to mind 1999. That was when the staggering ISL (International Sport and Leisure) Worldwide-ATP marketing, broadcasting and licensing agreement for “elite” tournaments was made. It was a ten-year arrangement for $1.2 billion. Unfortunately, ISL collapsed in May 2001. Oops.

Canada’s performance was stellar in reaching the final against Spain. Because of the “fairy-tale” quality that had been part of its success, “The Great White North” was looking to join Australasia, Croatia, Serbia, South Africa, Sweden and US each of whom took home the Davis Cup in its debut.

Unfortunately, having won the tie five times since 2000, the home country was a prohibitive favorite to earn number six. That Spain closed out the inaugural Pique/Kosmos/Rakuten/ITF Davis Cup, 2-0, wasn’t surprising. As a result, the Canadian first-timers joined Japan in 1921, Mexico in 1962, Chile in 1976, Slovakia in 2005 and Belgium in 2017 as debut finalists and history’s runners-up.

With 24 years more to go, the new Davis Cup has potential. Still, the tennis world is trusting that the future offers more than just a quote from Bob Dylan, the 2016 Literature Nobel Prize winner. Dylan, who many regard as the world’s poet laurate said, “Money doesn’t talk, it swears.”

And a big budget doesn’t necessarily make it better. It just makes it happen. One can only hope that what seemed like a week-long exhibition will become more organized, less confusing and a tribute to the Davis Cup tradition.

A Special Remembrance

Mark Winters

mwinters@nsmta.net

November 2019

Gardnar Mulloy Photo International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport Rhode Island

In 1954, Armistice Day became Veterans Day. It was a day to honor all the US military veterans who served their country. It should not be confused with Memorial Day, which recognizes all those who perished while safeguarding the nation.

Armistice Day had originally been called Remembrance Day. It was first observed in 1919 in the British Commonwealth, recognizing the armistice that concluded World War I on Monday, November 11, 1918 at 11:00 a.m. The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month is especially significant because it ended what had been thought to be the war to end all wars. Sadly, it wasn’t, but the day has been set aside to honor those who helped keep the world safe from tyranny.

An all-star collection of tennis players served their country during World War II. Few, though, could match the exploits of Gardnar Mulloy. He was a naval officer who commanded a LST32 (Tank Land Ship) in the Mediterranean during the European campaign. In 2015, the year before he passed away, he received the French Legion of Honor, an accolade presented for his involvement in the operations that took place in Italy and the Provence area of France. The recognition made Mulloy the oldest recipient of the order since it was created by Napoleon in 1802.

In “The Liberation Of Roland-Garros”, an article by Guillaume Willecoq that appeared April 4, 2018 on the website rolandgarros.com, Budge Patty revealed, “I experienced the liberation in Paris as a soldier in the 5th Army returning from Italy. I returned to the United States in January 1946…and soon hurried back here [Paris] five months later. I was 18 and wanted to be grown up - to study. I was actually heading to university when I got my mobilization orders. But after the war, you couldn’t hope to do that anymore. I lost two years of my life because of the war, and like all the young people in my generation, I had lots of things to catch up on.”

Budge Patty Photo International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport, Rhode Island

Patty offered Willecoq an interesting aside remembering, “At the time, you had to make do and mend, and we were certainly pleased to use the army-issue shorts as we had nothing else to wear.”

The long-time Lausanne, Switzerland resident was nicknamed “Budge” by his brother because, as a youngster, he was lazy and wouldn’t budge. In time, he became known for playing stylishly and dressing elegantly. He combined both of these attributes with movie star good looks. In 1950, he added his name to the record books by winning Roland Garros and several weeks later taking the Wimbledon title. Only Don Budge, in 1938, and Tony Trabert, in 1955, have achieved the same back-to-back slam double.

In 1957, at the age of 33, Patty added to his acclaim by teaming with Mulloy, who was, by the standard of the day, an astonishing 43 years old. They defeated Australians Neale Fraser, who was 23, and 22-year-old Lew Hoad, 8-10, 6-4, 6-4, 6-4 for the Wimbledon Doubles championship. The duo was the oldest team to claim a major title at that time.

The history of WWII is filled with captivating stories. One of the most endearing is about Tom Brown. He spent the much of the conflict in a tank… with a tennis racquet. He never really said if the racquet served as a constant reminder of his pre-war on-court success or if it was simply provided good luck or if it went on to inspire him at Wimbledon in 1946. However, after trading his Army khakis for white tennis shorts, he was a Wimbledon semifinalist, losing to Frenchman Yvon Petra 4-6, 4-6, 6-3, 7-5, 8-6. (Brown didn’t go home empty handed. He and Jack Kramer defeated Geoff Brown and Dinny Pails of Australia, 6-4, 6-4, 6-2 in the doubles final.)

Tom Brown Photo California Athletics Hall of Fame

Petra was the last Frenchman to win Wimbledon and the last men’s champion to wear long pants in The Championships final. In the trophy round, he defeated Geoff Brown, 6-2, 6-4, 7-9, 5-7, 6-4. It was a memorable outcome since he had been a German prisoner of war for two years after being captured in 1940, in Alsace, France during the invasion. Attempting to avoid capture, he seriously injured his left knee. Ironically, because he had competed in Germany before the war, he was known, which resulted in a doctor being sent from Berlin to treat his injury.

Lee Tyler, Brown’s longtime companion in his later life, responded to questions about the “tank racquet” admitting, “Tom Brown of San Francisco was the reigning tennis champ of Northern California when he joined the Army at the age of 20. He truly believed in tennis as a way to world peace. So, it was only natural that he packed his racquet along wherever he was sent. He was trained to be a mortar gunner and in February of 1945 was shipped to Europe with the 20th Armored Division of General George Patton’s Third Army. He was fortunate. The war was beginning to wane as they tramped through Southern Germany, Austria and France where he was assigned to a half-track.

“Nosing beneath the floor boards, he found enough space for his racquet. And there it sat, protected and ready for action. That summer his unit was sent home and he went to get his racquet. It looked okay but wasn’t. Two string settings had popped. Regretfully, he tossed it away.”

But there is more to the saga. Tyler happily recounted, “Tom’s army days also included condoms – they were free. Evidently the more the better. He built up a supply, thinking they might come in handy someday for something. True, they did just a year later. In 1946, he was named to compete at Wimbledon. He went over by ship, and had five racquets, all strung with the highest grade of expensive gut. How could he protect them from the wet sea air? Voila! He remembered the condoms. A friend helped him pull them over the racquet heads. First thing he did in London was to strip them off. The wooden frames and gut strings were just fine.”

Art Larsen Photo Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport, Rhode Island

Art Larsen, who was nicknamed “Tappy” because of his habit of tapping things for good luck, played competitive tennis for therapy after WWII. A talented lefthander, he was mentally scarred because he participated in the landing at Omaha Beach on D-Day. Following the war, he recalled the terror of watching US planes mistakenly bomb US troops thinking they were German forces. He admitted after surviving without a scratch, his behavior became even more eccentric because he had witnessed the terror having served at the front for three years. (Then they called his condition shellshock, but now it is referred to as PTSD.

It is impossible to adequately pay tribute to all of those who, over the years, have made their country better through military service. In early September, the US Open took a monumental step by recognizing those in the services by celebrating Lt. Joe Hunt Military Appreciation Day. (Hunt was the 1943 US National singles champion who lost his life when his Navy Hellcat, a WWII combat aircraft, went into a deadly spin on a training flight off the Florida coast in early 1945.)

Joe Hunt Photo International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport, Rhode Island

But, there are so many others who have been overlooked. Individuals who put their lives on the line around the world, in places like Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf Wars and Afghanistan to name but a few of the conflicts since WWII. Each of these individuals, in their own way, are heroes. Over the years, many died but, and this the essential issue, so many returned. They have attempted to slip back into civilian life unsung and unrecognized, forced to ignore the scars that often don’t show. Anyone who served his or her country should be recognized every day, because they are the reason we can breathe free.

They are among us twenty-four/seven and deserve much more than one day a year worth of gratitude. They should never be forgotten because they sacrificed so much so that we can live.

Allie Ritzenberg - Washington D.C. Tennis Legend

Billy Crawford

billyecrawford@gmail.com

November 2019

Allie Ritzenberg Photo Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post

Albert “Allie” Ritzenberg lived to be 100 years old. During his lengthy life he became a legend both on and off the court.

Ritzenberg was born in Washington D.C. His father ran a hardware store and later a salvage business. His mother was a homemaker. He, along with brothers Hy and Nate, became outstanding tennis players. In 1936, Nate and Allie won the D.C. high school doubles championship, and Nate defeated Allie for the singles title. As an 18-year-old Allie won the Middle-Atlantic Junior Championship and a number of other local and regional tournaments.

In December of 1935, it was clear that he would be a success after a Washington Post reporter, said he had spied, “a barelegged young man in a pair of midsummer shorts and a pair of woolen gloves” scampering around a tennis court completely “oblivious to the twelve degree (above zero) weather.”

It wasn’t in the least surprising that the youngster was Allie Ritzenberg.

As the Depression was ending, Ritzenberg entered the University of Maryland in 1938 and graduated with a BA in Sociology in 1941. While in school he played No. 1 on the tennis team, losing only four intercollegiate matches.

With the start of World War II, he entered the Army Air Force as a private. After spending 27 months with the 380th Bombardment Group in Australia, New Guinea and the Philippines, he was discharged, having risen to the rank of captain. Following the war, he did graduate work in Sociology at George Washington University. He received a master's degree while continuing to focus on tennis.

"I was a ‘restless-youth’ type, twenty years before that style became popular," he told Sports Illustrated. "I wore my hair long, ate vegetables, batted around in scruffy clothes. I knew what I really wanted to do was stay with tennis."

Allie Ritzenberg Photo Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post

He established the first Washington area indoor courts in 1945 – Cabin John Indoor Tennis in Bethesda, Maryland. He was President and owner of the club until 1953. The same year (1953), he began the first of two years spent as the Georgetown University tennis coach. He was the Director and Head Professional at St. Albans School & Tennis Club in Washington, on the grounds of the National Cathedral, where he coached generations of students beginning in 1962.

In addition to the boys at St. Albans, Ritzenberg shared his teaching magic with First Lady Jacqueline (Jackie) Kennedy, George H.W. Bush, Chief Justice Earl Warren, Kay Graham, Robert McNamara and other members of the city’s elite. He also spent time working with former Wimbledon champion Pauline Betz Addie.

For more than eight decades, he remained a fixture in the Washington tennis world, working to popularize the sport. At one point, there was a ten-year waiting list to join his club, which was among the first in the Washington area to prohibit discrimination based on race, religion or sex. He went out of his way to democratize tennis in the inner city and the suburbs. He trod on this same enlightened path on State Department tours to Haiti, Libya and other countries.

Along his journey, he authored numerous articles which appeared in the Washington Post, Tennis Magazine, Health, Recreation and Physical Education and the New York Times.

He served as President of the Middle-Atlantic Professional Tennis Association and Vice President of U.S. Professional Tennis Association (USPTA). He was elected to the following Halls of Fame: Washington Area Tennis Patrons Foundation in 1983; Middle-Atlantic in 1996; The Greater Washington DC Jewish Sports in 1995; Washington Tennis & Education Foundation in 2014.

In 2004, Ritzenberg completed “Capital Tennis: A Memoir”, which is a captivating read. In Chapter 4, he explained his interest in playing senior tournaments, saying, “Playing on the senior tour has given me a chance to prove myself, because I became a teaching pro early, from 1962-2005, at St. Albans School & Tennis Club.

"I had to give up amateur competition and never had a chance to make it big. So, with the senior tour I decided to thrown my hat in the ring and play against and with some of the big names in amateur tennis.”

On the senior circuit, he won eleven International Tennis Federation World titles and earned the ITF Men’s 85 No. 1 ranking in 2005. He was a member of five USTA International Tennis Federation Cup teams including: Men’s 55 Austria Cup, Men’s 65 Britannia Cup, Men’s 70 Crawford Cup and Men’s 75 Bitsy Grant Cup. Over the years he played senior tennis in Switzerland, Israel, Spain, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Soviet Union, Poland, Monte Carlo, Brazil, England, Argentina, Mexico, France, Estonia, Australia, and Chile.

Throughout his adult life, Ritzenberg was devoted to tracking down and purchasing tennis antiquities and tennis-inspired art. Much of his collection is now on display in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island. Nicole Markham of the International Tennis Hall of Fame, who is the Curator of Collections, pointed out that the Albert and Madeleine Ritzenberg Collection was acquired in June 2004. She said it covers virtually the entire history of tennis from the Renaissance through the 1930s. It documents both how far back in time tennis goes, and the extent to which tennis imagery has become part of our culture. The 2,250 plus objects in the Collection, gathered in half a century of travels around the world, represent the passion of [a] well-known Washington, D.C. tennis pro Allie Ritzenberg and his wife.

“When we first started collecting, it was because we loved tennis,” Ritzenberg stated. “But as time went on I came to realize that we were building something original and that assembling this collection was a creative act.”

Albert “Allie” Ritzenberg, who was born November 11, 1918, passed away November 22, 2018 at his Bethesda, Maryland home due to respiratory failure, was a very rare individual. He, in the true sense of the word, is now a legend.

J. Emmett Paré – Still Remembered

Billy Crawford

billyecrawford@gmail.com

September 2019

Every area in the country has players who have been outstanding on court and equally impressive working in the local tennis community. With the passage of time, many of these special individuals have been forgotten by all but a few. J. Emmett Paré is an example.

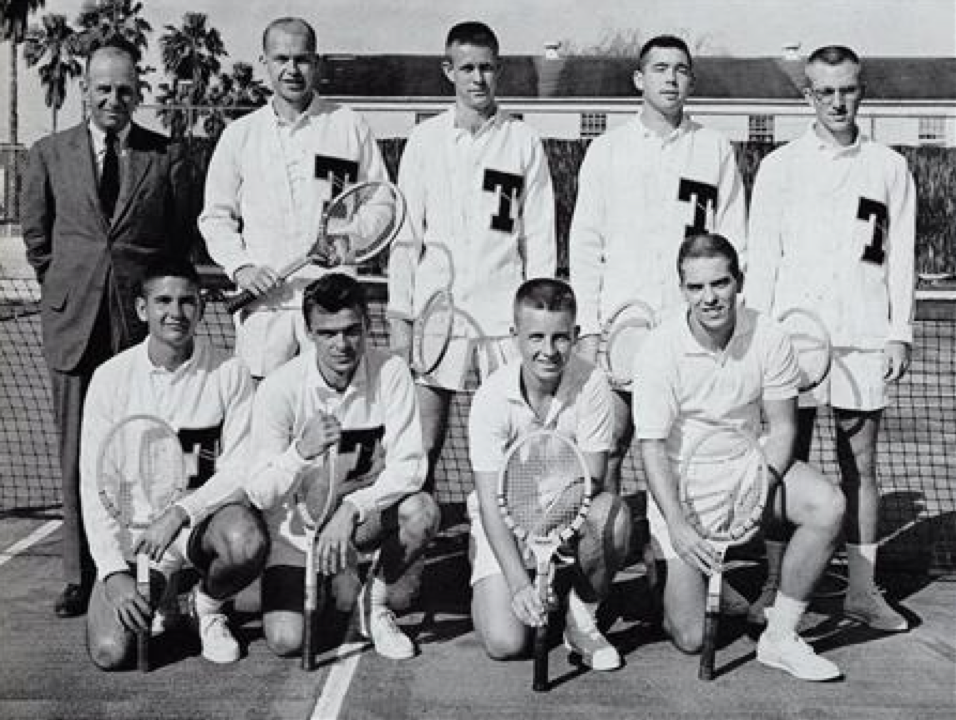

In 1934, Paré became the men’s tennis coach at Tulane University in New Orleans. He held the position for 39 years (interrupted by World War II when he served in the US Navy as a Lieutenant Commander.) After the war, he returned to Tulane and also served as Head Professional at the New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club. During his tenure as the “Green Wave” coach, Tulane’s record was 285-61-19. In 1949 and again in 1957, the team was an NCAA finalist. In 1959, the school won the NCAA Team Championship.

Moving from team to individual success, his players won eight singles and two NCAA doubles titles. As good as the squads were nationally, they were even better regionally, securing 20 Southeastern Conference Championships.

William (Bill) Tilden, Jr., wrote this about Paré in Match Play and the Spin of the Ball in the second edition of his classic book published in 1925. “I must mention at this place the sensation of the 1924 junior season – Emmett Paré of Chicago. [He is] in my opinion the first great natural player the Middle West has produced in over a decade. He seems destined for mighty works.”

True to the prediction, (the year the book was released) , Paré, a student at Saint Mel High School, a Christian Brothers all-boys school in Chicago, was the singles winner at the University of Chicago Interscholastic Tennis Tournament.

A year later (1926), he entered Georgetown University in Washington DC. He eventually became captain of the tennis team. As a player, he flourished, winning the Western Indoor Championship, the Michigan state title and the Tri-State Tournament in Cincinnati. In 1929, he and Georgetown teammate, Gregory Mangin, reached the NCAA Championships doubles final.

After graduating from the university, he won the US National Clay Court Championship in 1930. During his career, he competed against many of the best players in the game. Among his opponents were future International Tennis Hall of Fame honorees such as Rene Lacoste, Wilmer Allison, Frank Shields, Frank Hunter, John Doeg, Bryan “Bitsy” Grant and Tilden.

In 1931, Paré joined the original Tilden Tennis Tours, Inc. He often opened the traveling tennis show playing the first match against Hunter. Tilden would then face Karel Koželuh in the feature contest. The tour began at Madison Square Garden, February 18, 1931, with approximately 14,000 in attendance. From there, matches (one-night stands) were staged in Baltimore, Boston, Cincinnati, Youngstown, Columbus, Detroit, Chicago, Omaha and Los Angeles.

Lester Sack, a Tulane tennis team member from 1955-1958, remembered Paré, “He was a very classy guy. I remember he wore a coat and tie to practice almost every day. Only when he went on the court to play did he wear tennis attire. He could play the game, coach the game and teach the game.”

Ron Holmberg played for Tulane between 1956 and 1959. He wrote about Paré, noting, “I, for one, feel very lucky to have been able to play for such a coach. A very demanding taskmaster; a brilliant tennis mind to explain the game very simply to you; a person who held academics at the very highest priority and a friend all wrapped up in one very humble person who instilled striving for excellence on every occasion. He truly cared for and took care of his players.”

Linda Tuero was the first woman to receive an athletic scholarship at Tulane. She played on the “men’s” tennis team. While in school, she also competed on the women’s professional tennis circuit, (but didn’t accept prize money in order to maintain her amateur status).

She recalled, “I feel privileged to have had Emmett Paré as my coach and mentor. I was fortunate to pass his ‘tryout’ at the age of 11, and I never forgot the opportunity I had been given and what was expected of me. To this day, I remember my lessons so very well. His favorite technique was imitating your bad strokes. If I pulled away on my backhand and let the racquet head drop, he would demonstrate it in painful detail.”

Tuero continued, “He told me over and over and over – sixty percent of the game is footwork. All this help was instrumental to my winning the nationals at 14, 16 and 18. I was honored that he was present at the 16s in his hometown of Chicago.”

After Tuero graduated from high school, Paré offered her a scholarship. It was a landmark decision and it made Tuero one of the few woman, in those days, to be part of a men’s tennis team.

“But Coach Paré was courageous enough to do that,” she admitted. “He would still work with me in the summers and was instrumental in my winning the National Women’s Clay Courts in 1970. He continued to work with me after I became a professional. I was a quarterfinalist at the French Open (Roland Garros) in 1971 and won the singles title at the Italian Open in 1972. I would return home to New Orleans with my ‘scrapes and bruises’, and he would re-adjust my game back to the fundamentals he had given me. I am certainly proud to have played at the top of my profession, but I don’t for an instant think I could have done it without Coach Paré’s direction.

“I treasure so very dearly all my sessions with Coach, and he has left an indelible mark on my life. I know for a certainty that his teaching philosophy, personality and courageousness were what inspired me to reach my lifelong goals in tennis – both as an amateur and a professional. That influence has lasted my entire life.”

Paré, who passed away in New Orleans on October 8, 1973, was inducted posthumously into the Southern Tennis Hall of Fame in 2012. He joined the following former players from his Tulane teams who have been similarly honored including Hamilton (Ham) Richardson, Clifford Sutter, Crawford Henry, Wade Herren, Linda Tuero, Ernest Sutter, Leslie Longshore, Lester Sack, Ron Holmberg and most recently Jack Tuero.

US Open Military Appreciation Day – A Story About “Two Joes”

Mark Winters

mwinters@nsmta.net

September 2019

This article was originally published on UBITennis.net, September 9, 2019

Joe Hunt and Jack Kramer

Photo Courtesy International Tennis Hall of Fame Museum Newport Rhode Island

In early July, the USTA announced that it would recognize a former champion on the day it annually fetes those who have dedicated portions of their lives to serving the country. There is a great deal more to story about the decision for the US Open to celebrate Lt. Joe Hunt Military Appreciation Day. It is much bigger than resolving to honor the 1943 US National singles champion whose extraordinary accomplishments have, for the most part, been lost to all, but a few who cherish the game.

In truth, this is a story about two “Joes”. But, it is much more meaningful then the days when “Joe” was slang for a good guy. It is more significant than a reference to an American soldier, and it surely does not relate to a mere cup of coffee. These Joes are special. They are distinctly different, yet very much alike. One easily could be a movie character straight out of Hollywood’s “Golden Age.” The other seems to be a regular Joe but has proven to be much, much more.

The first Joe is Joseph (Joe) R. Hunt. He was born in San Francisco, California but raised in Los Angeles. He had it all. Based on his looks alone – he was blond and blue-eyed and built like he worked out at Muscle Beach in Venice, California rather than on the Los Angeles Tennis Club courts-he was ready for the “Big Screen.”

However, there was a problem. He was also a great athlete. He won the National Boys’ 18 and 15 titles. By the time he was 17, his playing ability earned him a 1936 US Men’s Top 10 ranking. Playing No. 1 for USC, in 1938, he never lost a team singles or doubles match. He rounded out the season taking the NCAA Doubles Championship with teammate Lewis Wetherell.

He teamed with Jack Kramer in the 1939 Davis Cup against Australia. With the US leading, 2-0, the youngsters came up short in the critical match. John Bromwich and Adrian Quist, a veteran duo, triumphed 5-7, 6-2, 7-5, 6-2. (Australia, in the only time the country ever trailed 0-2 in the final, ended up claiming the Cup, 3-2.)

At the US National Championships played in Forest Hills, New York, that same year, Hunt was a singles semifinalist losing to Bobby Riggs, the tournament winner, 6-1, 6-2, 4-6, 6-1. In 1940, he was again a semifinals and Riggs again ended his run, narrowly slipping past him, 4-6, 6-3, 5-7, 6-3, 6-4.

Hunt was almost too good to be true. Besides his good looks and being a stellar player, he had charisma. And, people really liked him. What’s more, he was exceedingly realistic. He was aware of what was taking place in the world during the late ‘30s. His concerns led him to leave USC and transfer to the Naval Academy in 1939.

Two years later, Hunt was able to garner time from his duties and became the first (and only) player from the Naval Academy to win the NCAA Singles title. His military commitment kept him from participating in the US Nationals later in 1941 and again in ‘42.

But, he returned to Forest Hills in 1943. World War II was ravaging Europe and the Far East, so the US was only Grand Slam tournament held that year. As it turned out, the final between Hunt and Jack Kramer was a contest between two players on “leave”. Hunt represented the Navy and Kramer, the US Coast Guard.

On a brutally hot and humid day, the Naval Lieutenant downed the Coast Guard Seaman 6-3, 6-8, 10-8, 6-0. For both players, it was a heroic performance. When Kramer’s last shot sailed long, Hunt collapsed on the baseline of the worn grass at the Forest Hills with leg cramps. His opponent, who had suffered a bout of food poisoning during the tournament, slowly made his way to where the winner was sitting to shake his hand. It was a dramatic end to an unforgettable match.

The second Joe is Joseph (Joe) T. Hunt. He is the great-nephew of the first Joe. As is the case with almost all of those in the family, he grew up playing tennis. For him, it was in Santa Barbara, California. By trade, he is a lawyer, and practices in Seattle, Washington. He is also a member of the Pacific Northwest, (one of the 17 USTA sections), Board of Directors and serves as the Section Delegate.

Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Photo Courtesy International Tennis Hall of Fame Museum Newport Rhode Island

Whenever he has an opportunity, Hunt heads to the court – not the legal one – but the one where he can play. He is as passionate about the game as he has been in leading the family’s effort to ensure that the first Joe isn’t forgotten. His dedication to this quest has been “Clarence Darrow-like.” As the clever 20th Century lawyer, pointed out, “Chase after the truth like all hell and you’ll free yourself, even though you never touch its coattails.”

Initially, Hunt sought to have “The Original” Joe’s name added to the Court of Champions, located between the South Plaza and Courts 10 and 13 at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. According to the USTA website, “The US Open Court of Champions celebrates the legacy of the greatest singles champions in the history of the US Open and US Championships. Each champion defines the essence of the talent and the character required to win at tennis’ ultimate proving ground. Inductees, selected by media from around the world, represent the tournament’s all-time greatest “the best of the best” whose electrifying performances have contributed to making the US Open one of the world’s top sporting events.”

The facts reveal that the Court of Champions was launched in 2004 and prior to 2019 only eleven more enshrinements had taken place recognizing ten men and eight women.

Joseph R. Hunt was killed on February 2, 1945, fifteen days before his 26th birthday. He was on a training flight when his Navy Hellcat, a WWII combat aircraft, went into a spin at 10,000 feet. It crashed into the ocean off the coast of Florida. His body and the plane were never recovered.

The second Joe has done his utmost to see that the first Joe would be remembered. It hasn’t been an easy. He has been focused on the task since 2013 and has been aided by the entire Hunt family. Still, it has been a slog. Borrowing from Navy slang, throughout it all, he has always been “Above Board.”

As an example of the way he is, Hunt delighted in revealing, “I know that Joe was not the only player to not have a chance to defend his US National title. Ted (Schroeder) won it in 1942 and was not able to defend in 1943. They both were Navy pilots stationed in Pensacola, Florida. Neither was granted leave to play Forest Hills in 1944 so they both entered a Pensacola tournament held at the same time as the National Championships. Of course, the local tennis community couldn’t believe their lucky stars to have the 1942 and the 1943 champions playing a local event. It was billed as the ‘Clash of Net Champions’ and would supposedly determine the true No. 1 player in the country, despite that ‘other’ tournament taking place in New York.

“Joe and Ted both reached the final where ‘urban legend’ has it that they played their match in front of thousands of spectators on September 4, 1944, while Frank Parker was playing Bill Talbert in the final of Forest Hills – and winning 6-4, 3-6, 6-3, 6-3. I have spent hours trying to vet the truth of this story.

I know that it is true, I just don’t know if it is 100% true that the two finals were played simultaneously. In any event, Joe beat Ted 6-4, 6-4. Despite what many have written, this was, in fact, the last tournament match of Joe’s life.”

Hunt pointed out, “Joe went out for football at the Naval Academy because he loved that sport too and wanted to be part of a team…”

Joe Hunt was a halfback on the Navy football team.

Acme Photo

But, as it is with many of the stories about the first Joe, there is much more to the tale…Imagine, in 1939, being one of the best tennis players in the country and, in the world for that matter, then deciding to play football and being assigned to the junior varsity. That’s what happened to Hunt. The next year, he played halfback on the varsity and was good enough to help the team achieve a six win, two loss, one tie season. In 1941, he was a standout on a team that finished with seven wins, one loss and one tie, and ended up ranked No. 10 by the Associated Press. Hunt played so well in the game against Army, (the Midshipmen’s third win in a row over the Cadets) that he was given a game ball signed by the entire team.

As mentioned in the beginning of this piece, Joe R. Hunt’s life, ( his death aside), was fairytale-like. As the second Joe recalled, “…He left his immensely successful life in Southern California to enter the Naval Academy, knowing that it would make it nearly impossible to achieve his dreams of becoming a great tennis champion… He put the right things ahead of the game.”

All of the Hunts are pleased that US Open Lt. Joe Hunt Military Appreciation Day will recognize a one-of-a-kind former tournament winner. Speaking for the Hunts the second Joe said, “The family of Lt. Hunt will be forever grateful to the USTA and the US Open leadership for taking this action to honor Joe by permanently assigning his name to the annual Military Appreciation Day.”

He further noted, “Connecting a real person to Military Appreciation Day will help the US Open achieve its inspiring purpose for the event, and there is no more fitting figure in the history of tennis to connect with the sport’s ideals of patriotism and sacrifice than Lt. Joe Hunt.”

Joe T. Hunt continues to believe that the first Joe’s life and the sacrifice he made for his country has earned him a place in the Court of Champions…and he also looks forward to collaborating with the USTA regarding how best to memorialize the lost aviator and other military service veterans at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center.

Simply said. during a divisive period in the world, people like Lt. is Joseph (Joe) R. Hunt need to be remembered and not covered by the dust that results from the passage of time.

Lt. Joseph R. Hunt, USN, training at Daytona Beach, Florida, where he was killed when his fighter plane crashed at sea.

Cover of the March 1945 issue of American Lawn Tennis

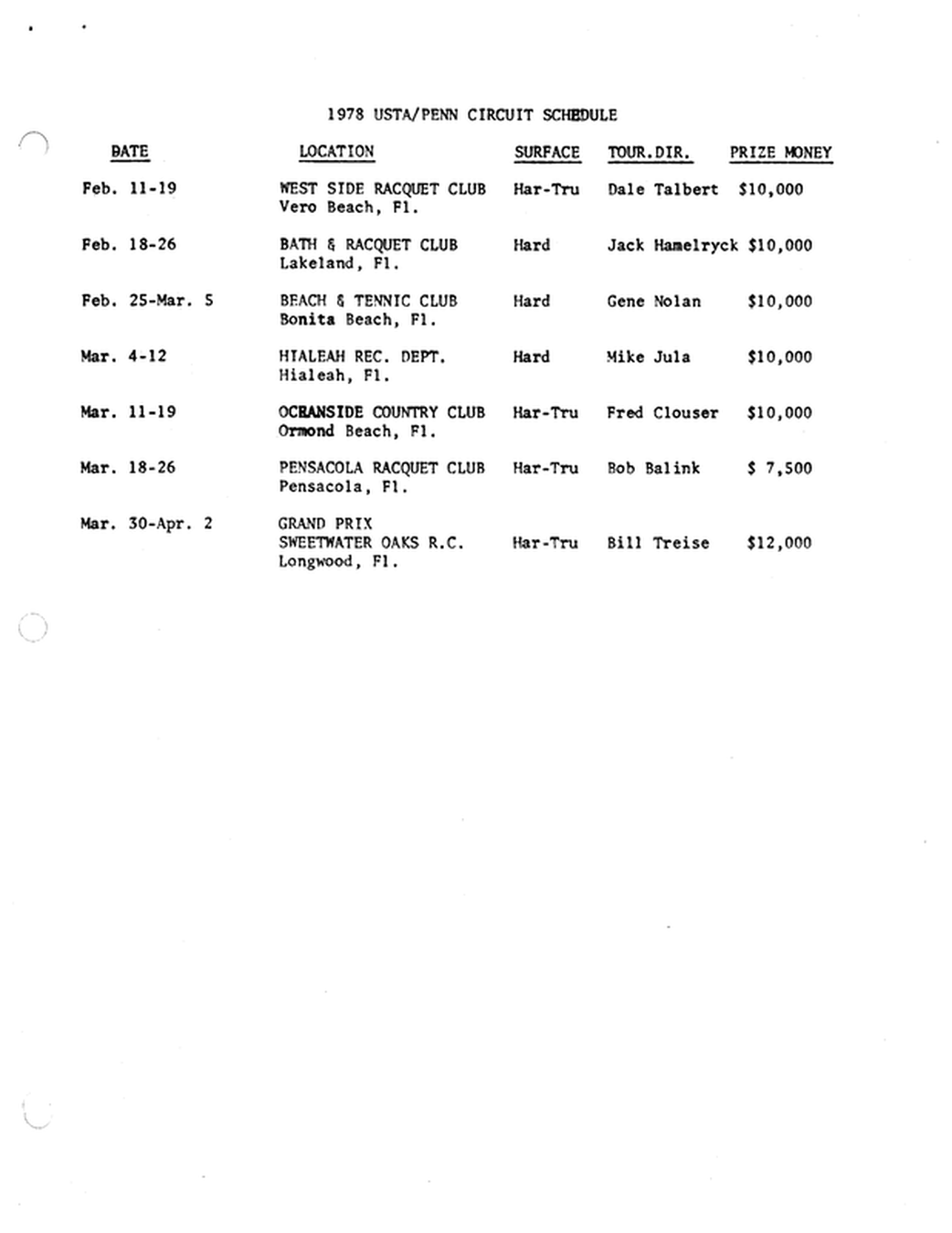

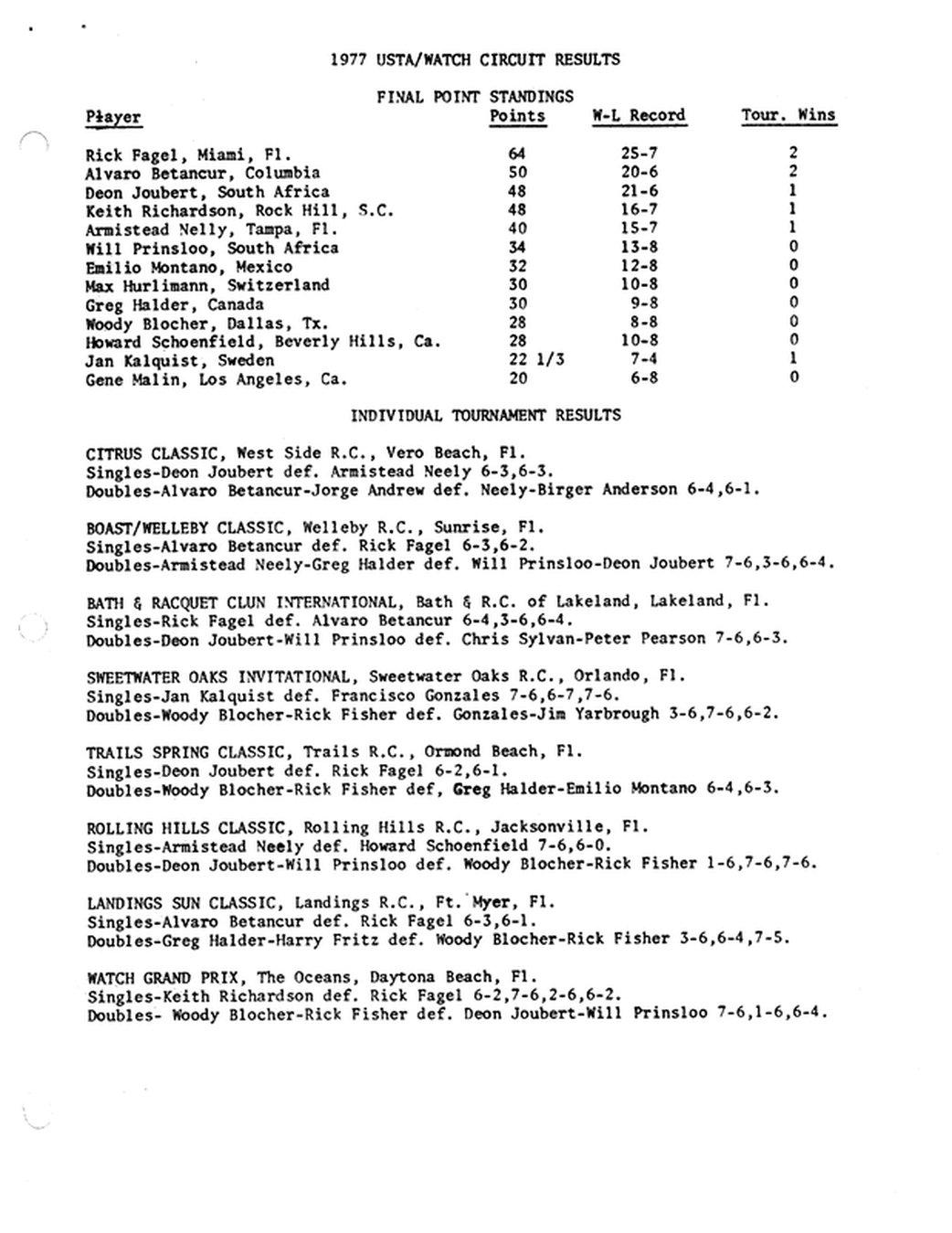

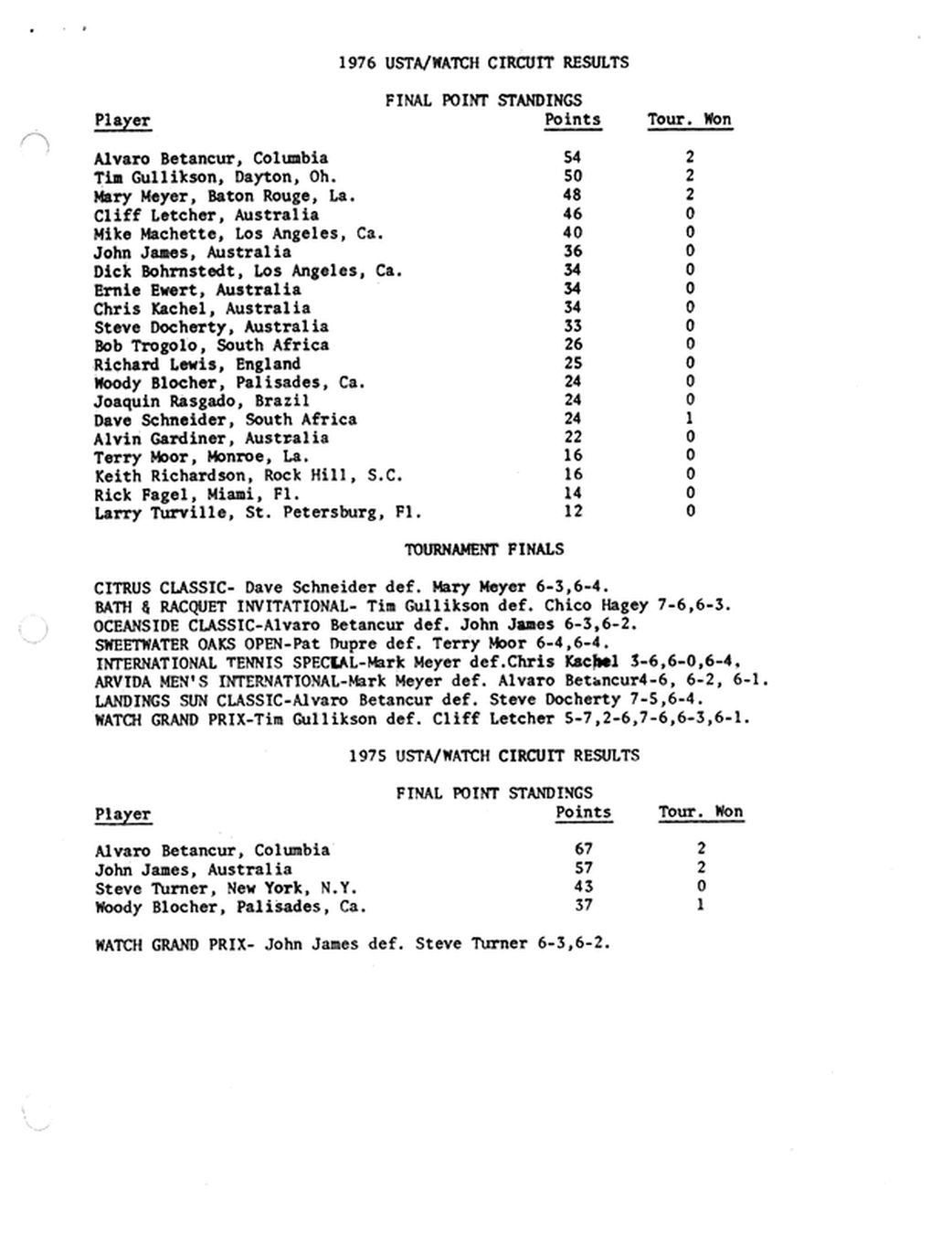

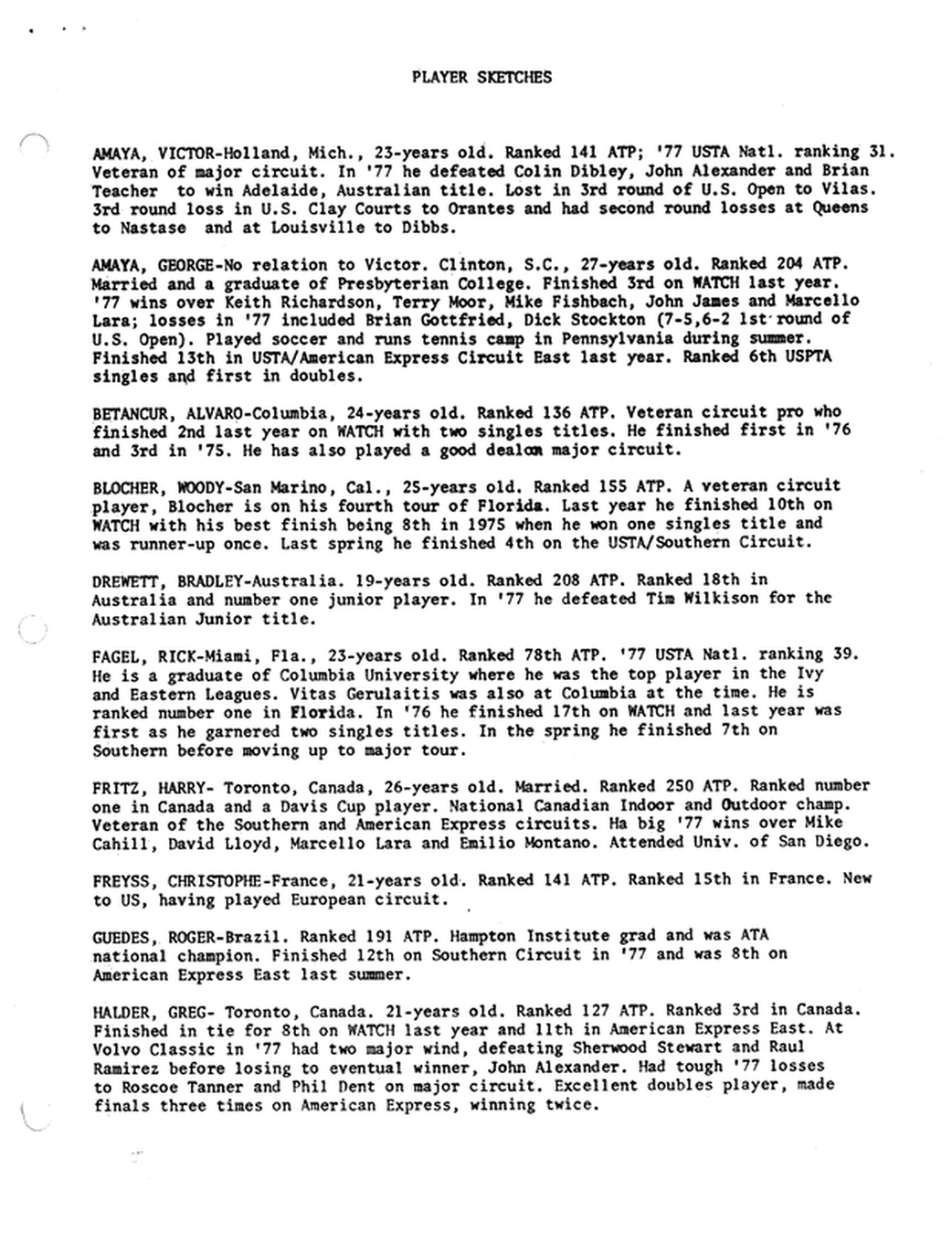

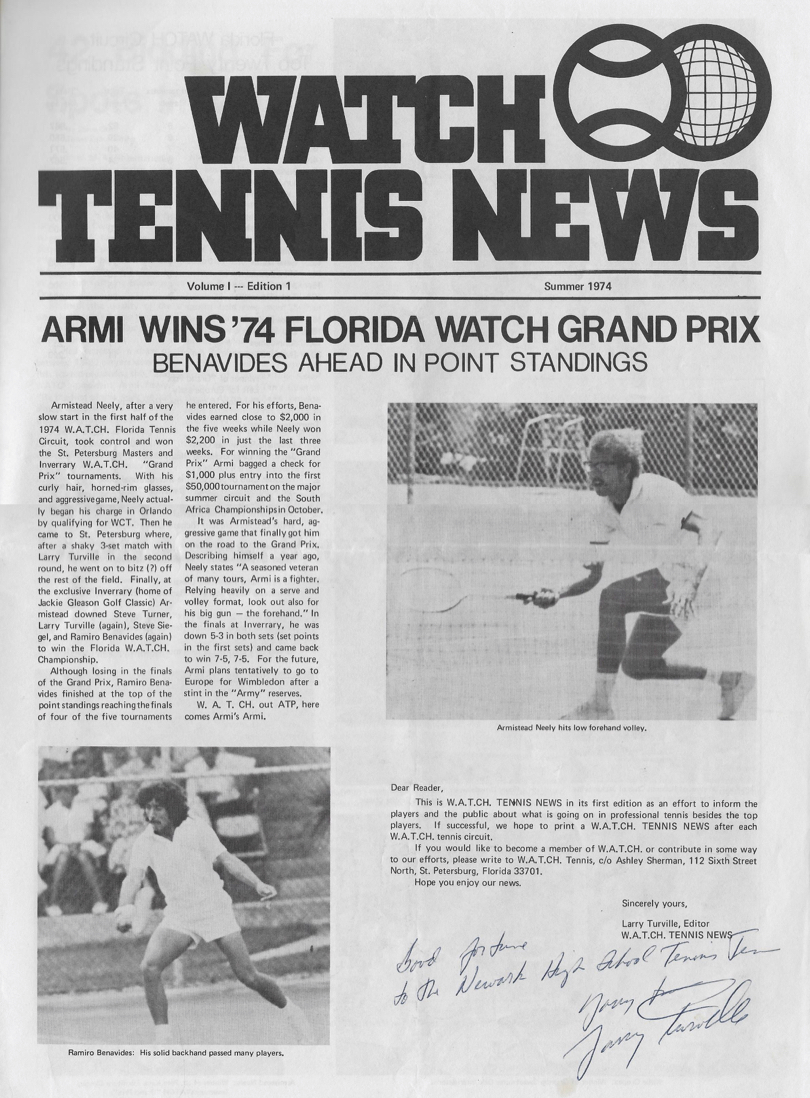

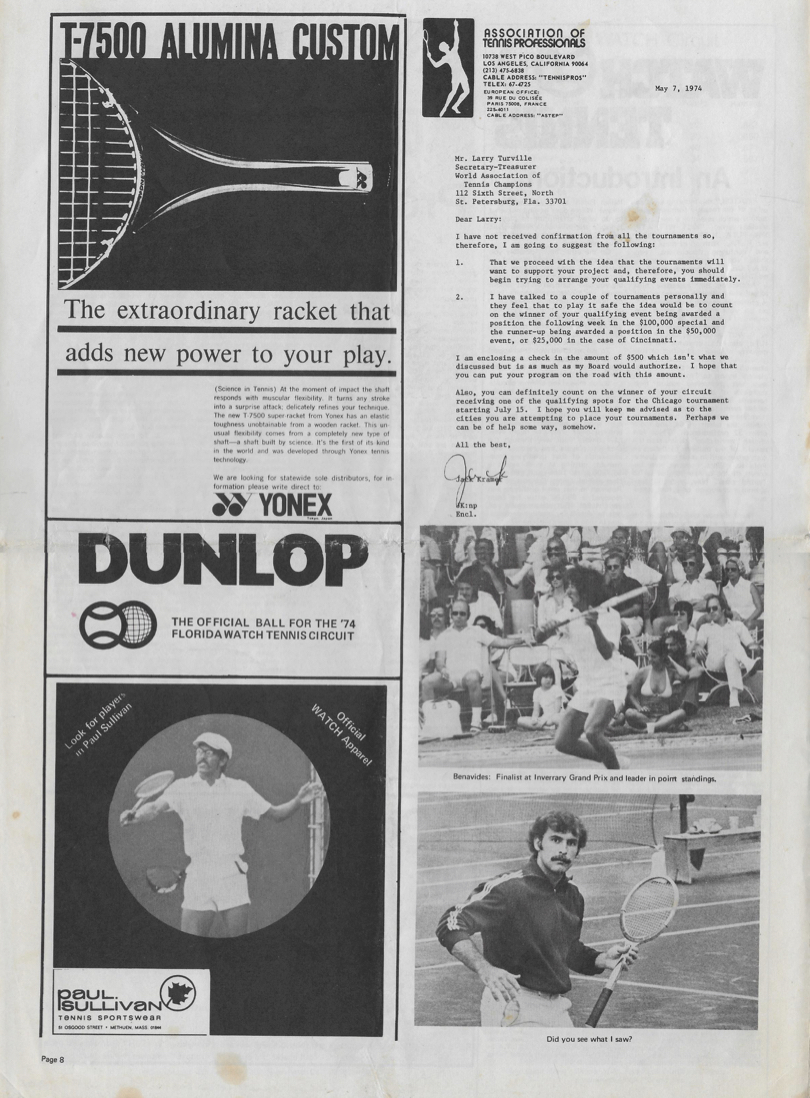

Turville And Neely Started The First ATP Satellite Circuit

Keith Richardson

krichardson19@gmail.com

June 2019

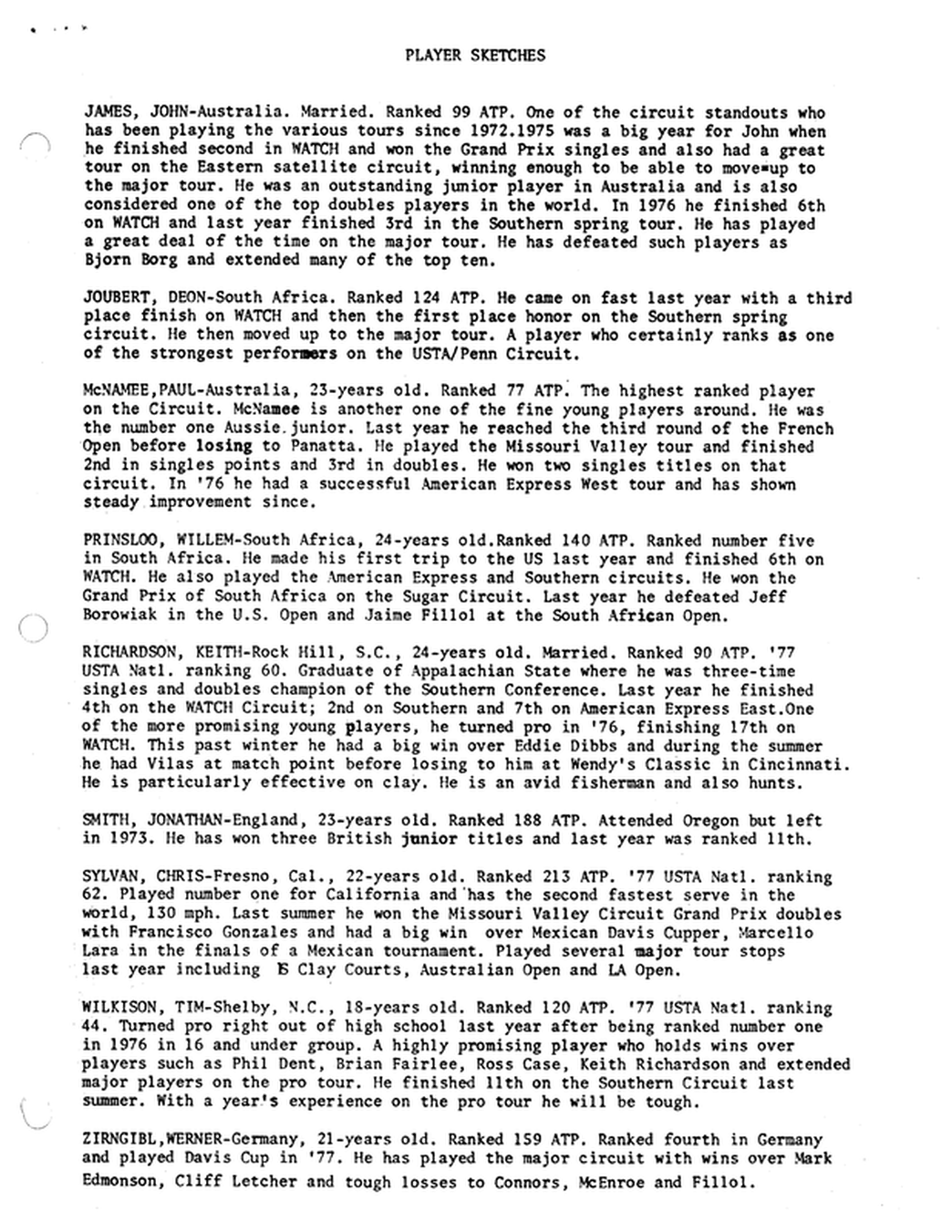

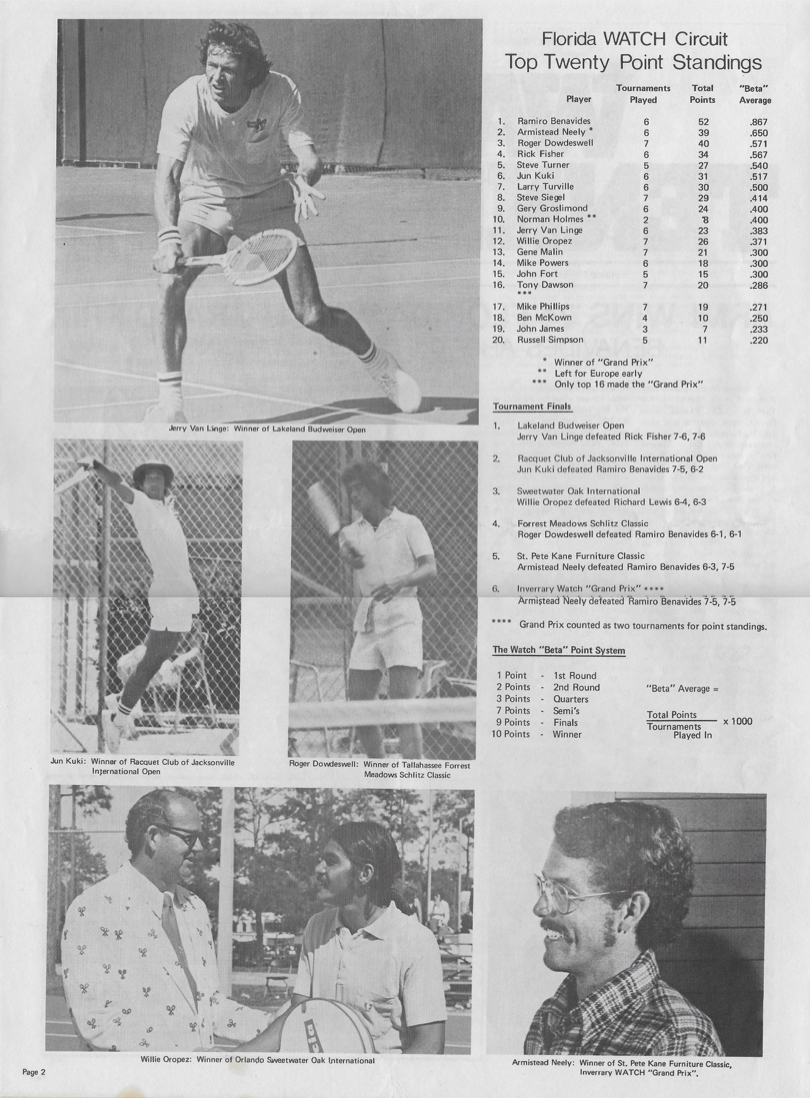

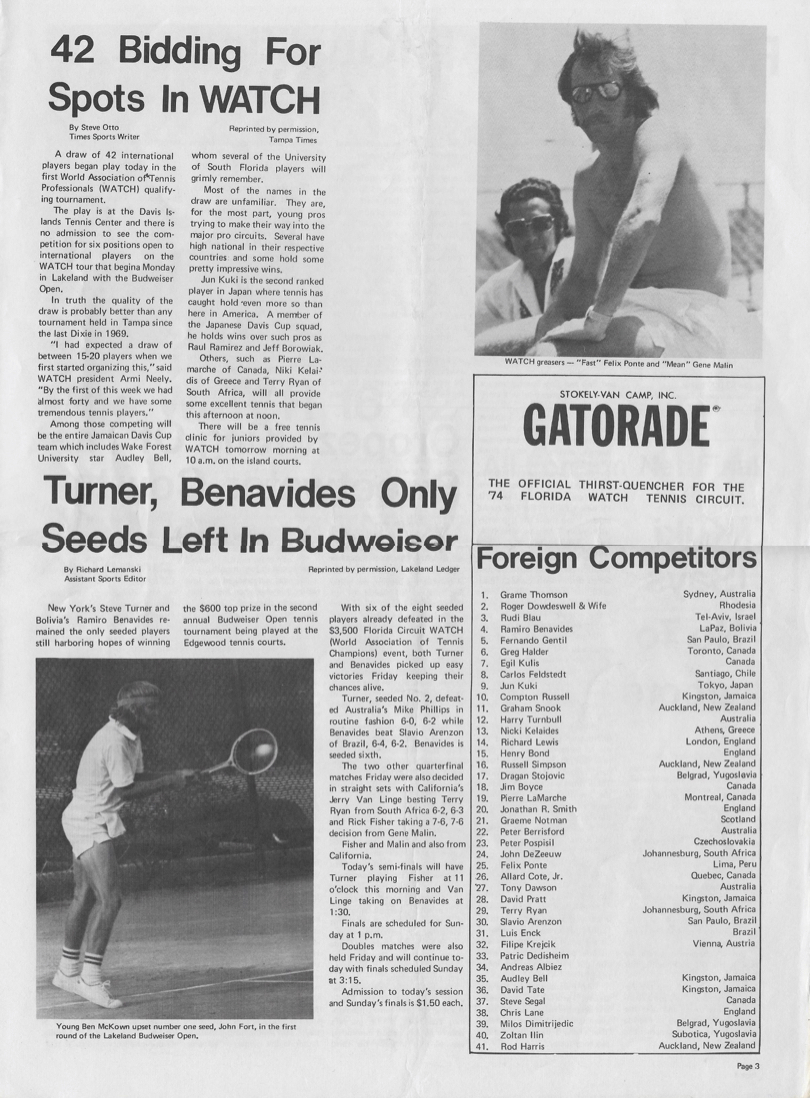

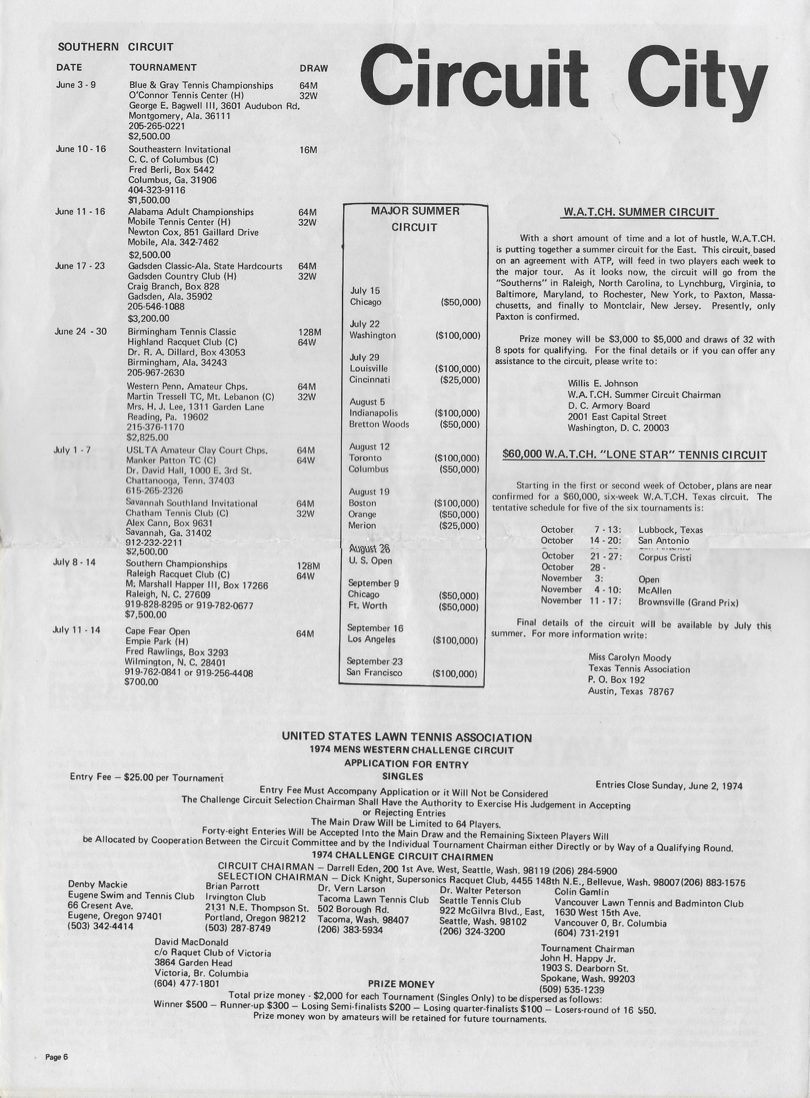

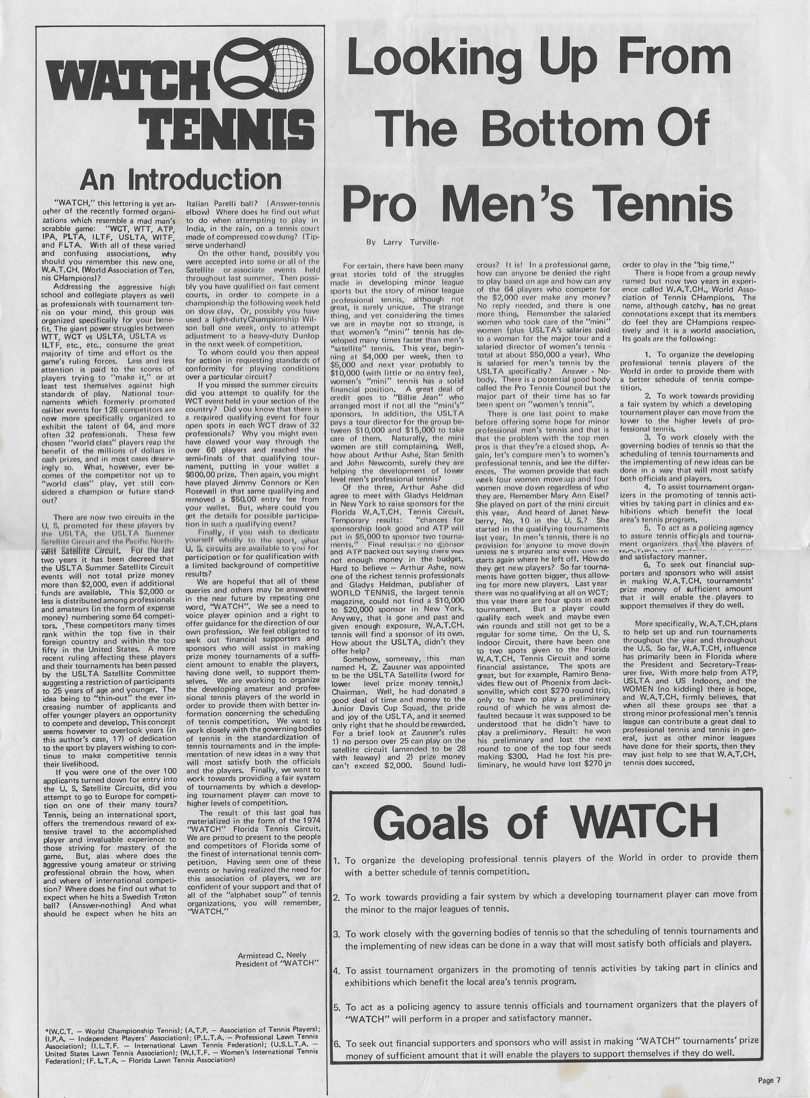

In the early 70’s, the up and coming tennis player who wanted to try his hand at professional tennis faced a dilemma – How to get into the big-time prize money tournaments requiring an ATP ranking. The big-time tournaments were the only events that offered the elusive ATP ranking points. It was a vicious cycle indeed. Thankfully for the 300 plus players worldwide that were unranked, Larry Turville and Armistead Neely came to the rescue.

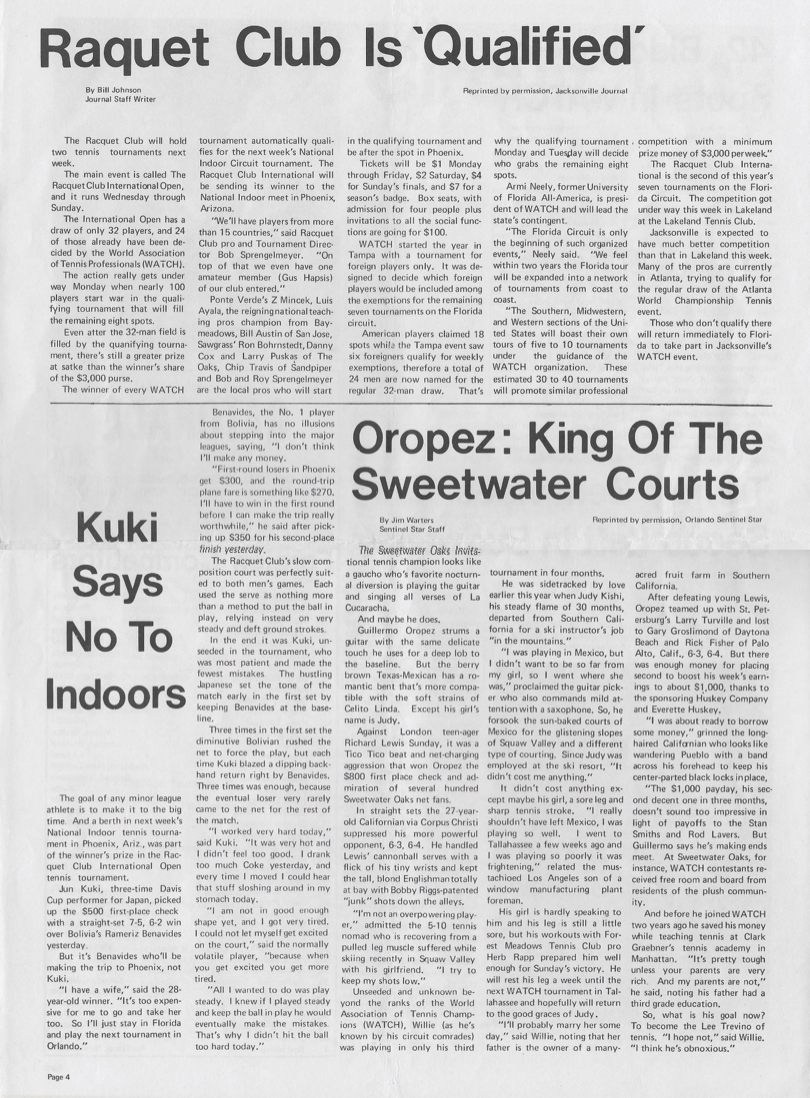

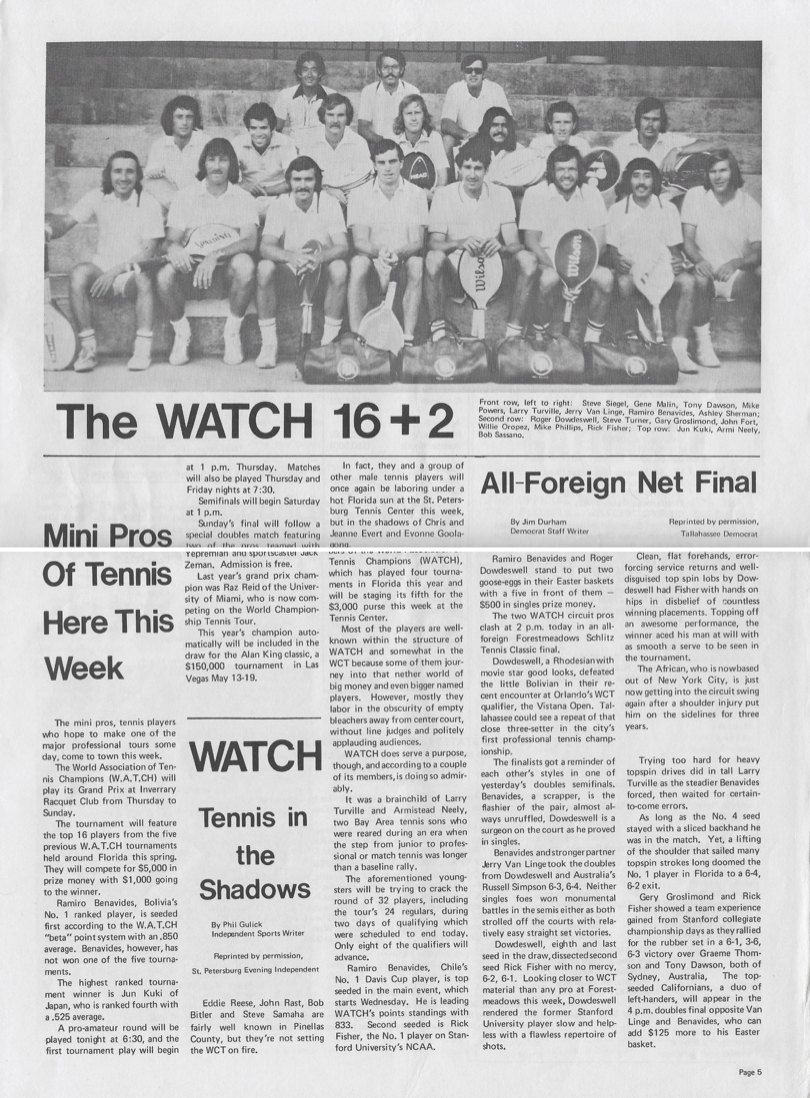

It all began in 1972 when Turville and Neely realized there was no clear path to breaking into the major tour other than showing up at a qualifying event prior to the tournament. Even then it was difficult to qualify for the qualifying event without points or without having an “in” with the Tournament Director. Ironically, Tournament Directors preferred foreign players who they thought were a better draw for spectators. The talent, in this second tier of aspiring pros, was unbelievably strong. Every player, including Turville and Neely, felt that on a given day they could compete with the big boys if they could just get into the big tournaments.

In the first year, Turville and Neely were able to enlist the help of Bill Riordan, President of the Independent Players Association Tour (IPA), which was an alternative to the ATP Tour. Riordan was intrigued by the idea of a circuit of tournaments that would wind throughout Florida from January to March with the winner and runner-up gaining entry to his Indoor Circuit the next week. Each tournament would have a draw of 32 players and would offer prize money of $2,500 (half from the host site sponsors and half from player entry fees, plus $500 from Riordan). The first year, the top twenty-four American players were directly accepted into the main draw based on their National ranking. The rest of the players, including the foreigners, were thrown into a qualifying tournament where the final eight players would gain entry into the main draw. Riordan liked the idea because he could count all the players on the Florida circuit as his associate members.

After operating as The Florida Professional Tennis Tour in 1973, Turville and Neely changed the name of the tour to “The WATCH Tour.” The acronym stood for “World Association of Tennis Champions,” and it became a badge of honor among players to say that they had played The WATCH. The new satellite tour was a success at the host sites because fans were getting a preview of some of the players that would soon be on the major tour. Even more important was The WATCH philosophy which stressed that the players needed to give back to the game to show their appreciation for the clubs hosting the events. To do this, each week there would be a Pro-Am, (which players were eager to play because they were guaranteed $50), and with some arm twisting, the players would give two free clinics a week, one for kids and another for women.

The circuit was an immediate hit with the players as they were able to hone their games during a usually dormant time on their schedules; get housing; and win a little money to boot! However, an important piece was missing: the chance to accumulate ATP points, providing a path to the major circuit. Turville flew to Los Angeles and met with Jack Kramer, President of The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), the organization that awarded points in the major professional tournaments worldwide. After Turville’s pitch, Kramer agreed that The WATCH warranted ATP points and asked Larry to draw up the format for how many points would be awarded based on the amount of total prize money for the circuit and number of tournaments.

A booklet was created detailing points, prize money, and the number of events needed to have a circuit. The minimum would be four tournaments and the max would be ten, followed by a Masters tournament for the top 16 finishers. After the completion of the Masters tournament, ATP points would then be distributed to the top 16 accordingly. The idea was that now countries all over the world could create these circuits. Finally, there was a way for the up and comers to get their first ATP points and, in time, move up to the major tour. The following year over a million dollars in prize money was available in satellite tournaments all over the world.

So, as the saying goes, the rest is history. At the same time, it must be remembered that The WATCH circuit ran for six years and was the first ATP recognized satellite tour. In the beginning Turville and Neely just hoped to have a place to play in the winter, but with the help of Bill Riordan and then the ATP, their vision created a clear path for players such as Johan Kriek, Heinz Gunthardt, Tim Wilkison, Tim and Tom Gullikson, and Andres Gomez to move from The WATCH to the major tour. It also allowed countless other players a chance to gain entry into tournaments all over the world and live the dream of becoming a touring pro.

The USTA first provided assistance in 1976 by funding a Tour Director position and took over running the circuit in 1980. David Grant, the Orlando Tournament Director, replaced Neely in 1974 and became the Executive Director of the Circuit. Shortly thereafter, Grant became President of PENN Tennis Balls and helped sponsor the circuit in 1976. Turville continued as the Tour Director until 1979. Today, there are no longer any satellite circuits like The WATCH, but maybe there should be a call for one like the one that Larry Turville and Armistead Neely began.

US Open’s Significant Numbers

Mark Winters

mwinters@nsmta.net

March 2019

This article was originally published on UBITennis.net, August 27, 2018

Photo courtesy International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport, Rhode Island

One of this year’s major US Open stories is in the numbers. The tournament is the fiftieth of the Open Era and the fortieth time it has been staged at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. But, for a select group of tennis devotees the August 27th until September 9th event is even more significant. It offers a “Lookback” opportunity, in truth a celebration, of Joe Hunt’s championship victory seventy-five years ago.

In 1942, Ted Schroeder slipped past Frank Parker in the US National Championships singles final, 8-6, 7-5, 3-6, 4-6, 6-2. A year later, Schroeder, in the military because of national preparation for World War II, was unable to defend his title. Joe Hunt took full advantage of the situation. In another All-American contest, on a brutally hot and humid afternoon, he defeated Jack Kramer for the title 6-3, 6-8, 10-8, 6-0 on the grass at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, New York.

When Kramer’s last shot traveled long, Hunt collapsed on the baseline and simply sat there, because he had leg cramps. His opponent, who had his own issues dealing with food poisoning during the tournament, was similarly exhausted. He, nonetheless, hopped the net then sat down next to the winner, and shook hands with him. Many years later, Kramer jokingly commented that although he was weak, if he had been able to last a bit longer, he may have triumphed by default.

Seventy-five years ago, the world was different. Beginning in 1939, World War II had devoured borders and changed Europe and Asia, (and not for the better). There were food and production shortages, and lifestyles were frequently altered. From a tennis standpoint, the annual fortnight in New York became a six-day tournament. The singles draws featured 32 players while the doubles had 16 tandems. Since many of the men were involved in military service, those participating in the event were not “match fit”. They hadn’t been competing since it was next to impossible to get leave from military commitments and, coupled with travel and gasoline restrictions, players were not focused on playing tennis tournaments. In fact, the US National Championships, (the only one of the four majors to be held during the war), had to rely on the government to release “limited amounts” of reclaimed rubber so that tennis balls could be made.

(Hunt would subsequently die fifteen days shy of his 26th birthday on February 2, 1945 when his Navy Hellcat, a WWII combat aircraft, crashed into the ocean while he was on a training flight off the coast of Daytona Beach, Florida.)

Photo courtesy International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum, Newport, Rhode Island

Hunt’s great-nephew, Joseph (Joe) T. Hunt grew up playing tennis in Santa Barbara, California. He is now an attorney practicing in Seattle, Washington and he takes advantage of opportunities to get on the court regularly. More important, he has led the family’s effort to ensure that Joe Hunt isn’t forgotten.

“I have to really spend some time to gather my thoughts on what the Seventy-fifth Anniversary of Joe’s victory means,” he said. “I have so many of them. Joe was a patriot from what is considered the greatest generation of our nation. He is the only American tennis champion to lose his life serving his country in a time of war. We lost him so early and so young. He never had a chance to reach his full potential, yet he accomplished so much by the age of 25. He was a remarkable young man, devoted to tennis, devoted to his family and devoted to his country. The family lost him, and tennis lost him. Over time, while the family continued to grieve the loss of our uncle, brother and son, tennis seemed to forget and not consider the meaning of this loss to the game.”

Tennis historians credit Kramer for developing the “Big Game” – meaning being a serve and volleyer. According to Bobby Riggs, a contemporary of his, Hunt used the tactic before the iconic Kramer.

“As maybe the first true serve and volleyer, Joe was changing the game itself,” his great nephew said. “He never had a chance to tell his story from his perspective. I feel I have been his only voice in trying to tell the tennis world who he really was and what we all lost.”

The original Joe Hunt was one-of-a-kind not only because of his athletic ability, but also because of his blond good looks and his marvelous charisma. As a junior, he was a star, winning the National Boys’ 15 and 18 titles. By the age of 17, his success on court earned him a US Top 10 ranking. In 1938, he was USC’s top player and didn’t lose a singles or doubles match. He enlisted and transferred to the US Naval Academy. In 1940, he was a halfback (American football) and played against Army that season, earning a game ball for his outstanding performance. The next year, he became the only competitor [ever] from the Naval Academy to win the NCAA singles championship.

Hunt continued, “Joe went out for football at the Naval Academy because he loved that sport too. He also wanted to be part of a team. He was the most famous player on the football team by a mile, and it wasn’t for football.” But, with all his stardom, he spent the hot summer and chilly fall getting pushed into the mud by seasoned players who wanted to make sure he knew he was no ‘star’ on their field. And he was fine with that. When he had the choice of skipping football practice so that he could play Forest Hills and possibly win it, he went to football practice. He would not let his teammates down, even though he was destined to spend more time on the bench than on the field as a backup running back. But, those on the football team respected him for it. They knew Joe’s tennis hands and legs were Davis Cup commodities and they saw Joe give them up for the team they were on. That is why they gave him the game ball for the 1941 Army Navy game, and every teammate signed it for him.

Photo Courtesy Thelner Hoover

“Now, after seventy-five years, the last remnants of the greatest generation are bidding farewell, and we as a nation are at a moment of moral truth. How are we to say goodbye to them? How are we to remember and honor them? How are we to protect their legacy of saving the world for future generations? Each soul lost in the war effort is a part of that legacy. How will tennis address this? We just saw a great remembrance of the return of the bodies of men who gave their lives in the Korean War. Bringing home, the bodies after so many years was hugely significant to the families and the nation. I think of Joe’s body, never recovered, at the bottom of the Atlantic with his plane. It’s a sadness our family still bears.”

The times were unparalleled, which makes it no surprise that an unmatched backstory resulted. “I know that Joe was not the only player to not have a chance to defend his title, because Ted (Schroeder) won it in 1942 and was not able to defend in 1943,”Hunt pointed out. “They both were Navy fliers stationed in Pensacola, Florida. Neither was granted leave to play Forest Hills so they both entered the local Pensacola tournament held at the same time as the National Championships. Of course, the local tennis community couldn’t believe their lucky stars to have the 1942 and the 1943 champions playing in the tournament. It was billed as the ‘Clash of Net Champions’ and would supposedly determine the true No. 1 player in the country, despite that ‘other’ tournament taking place in New York. Joe and Ted both reached the final where ‘urban legend’ has it that they played their match in front of thousands on September 4, 1944, while Frank Parker was playing Bill Talbert in the final of Forest Hills (and winning 6-4, 3-6, 6-3, 6-3). I have spent hours trying to vet the truth of this story. I know that it is true, I just don’t know if it is 100% true that the two finals were played simultaneously. In any event, Joe beat Ted 6-4, 6-4. Despite what many have written, this was, in fact, the last tournament match of Joe’s life.”

Seventy-five years was too long ago to remember for most of us. Memories and treasures from that time are scattered here and there. Some are lost forever. In the case of Joe Hunt, his accomplishments, along with the individual himself, should not be left covered in dust and diminished by the passage of time.

Great nephew Joe Hunt said, “I think of a young man who stood for literally everything that is true and good in sport. An amateur who wasn’t seeking to profit off his game. He left his immensely successful life in Southern California to enter the Naval Academy, knowing that it would literally make it near impossible to achieve his dreams as a tennis champion. He intrinsically understood sportsmanship, camaraderie and good will. Everyone loved Joe. He played for all he was worth, but never took a ‘win at all costs’ approach to tennis. He put the right things ahead of the game.”

Remembering Tennis' Own "Green Book"

Mark Winters

mwinters@nsmta.net

March 2019

This article was originally published on USTA.com, February 28, 2019

Photo Courtesy of Bob Sparks and Bob Thornton / International Tennis Hall of Fame